|

Table of Contents

Next

Chapter

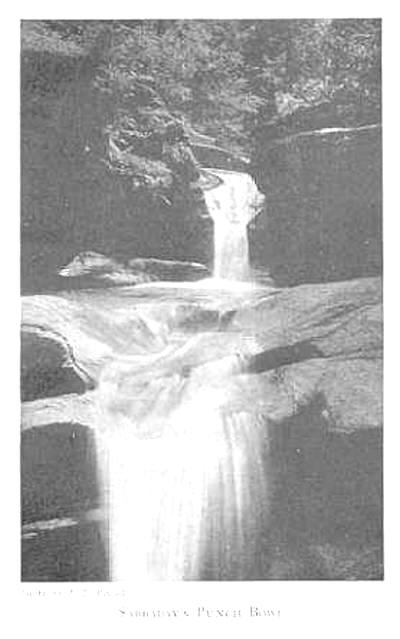

CHAPTER X SABBADAY'S TRIPLE FALLS By following the Swift River and Sabbaday Brook trails about a mile and a quarter from the former Passaconaway House (Shackford's), a charming triple waterfall on Sabbaday Brook is reached. This was, called by the early explorers of the valley Sabbaday Falls, because it was on Sunday that they reached this brook where the decision was made to return home.1 Sweetser calls the falls Church Falls, either because they were painted by F. E. Church, the artist―the picture being in the Woburn Public Library―or in memory of Charles Church, an early settler who lumbered near the falls.

There used to be an ancient foot-path, carpeted with dead leaves, leading from the open intervale up the Swift River. According to the legends of the valley, this was an old Indian trail, worn smooth by long and frequent use. The A. M. C. had placed signs, so that a visitor could find the falls unaided. In 1915, however, the lumberjacks so cut and slashed this historic trail as to obliterate it, leaving no trace of its famous "lightning tree," etc. By walking the lumber railroad and then following a logging road, one may now reach the falls, though by a route shorter and uglier than the old Indian trail. But the devastating ax did not stop at the trail. It injured Sabbaday Falls by so cutting the timber along the brook-bed above the falls that the watershed is now laid open to the merciless sun, and the volume of water pouring over the falls is greatly diminished. On the very edge of the flume, prone on the ground, lies a tree which must have been blown over in some hurricane. In falling, the tree lifted its roots out of their original bed in such a manner as to form a natural railing opposite the prettiest part of the falls. Juliet's Balcony is the name we have given to this parapet, and hundreds of visitors have leaned over it during the past twenty years. Few indeed are the persons leaving the Passaconaway valley without first having visited Sabbaday Falls.

Sabbaday offers numerous natural wonders; the ever moist sides of the chasm, the fall itself, its punch-bowl, and the Devil's wash basin still remain intact. Prof. Huntington gives this account of the falls, from the standpoint of an expert geologist: "The rock is a common granite, in which there is a trap-dike, and it is the disintegration of this, probably, that forced the chasm below where the steep fall now is. Above, just before we come to the falls, the stream turns to the west, and the water runs through a channel worn in the solid rock, and then, in one leap of twenty-five feet, it clears the perpendicular wall of rock, and falls into the basin below almost on the opposite side of the chasm. Great is the commotion produced by the direct fall of so great a body of water, and out of the basin, almost at right angles with the fall, it goes in whirls and eddies. The chasm extends perhaps one hundred feet below where the water first strikes. Its width is from ten to fifteen feet, and the height of the wall is from fifty to sixty. The water has worn out the granite on either side of the trap, so that, as the clear, limpid stream flows through the chasm, the entire breadth of the dike is seen. The fall of the water, the whirls and eddies of the basin, the flow of the limpid stream over the dark band of trap set in the bright, polished granite, the high, overhanging wall of rock, all combine to form a picture of beauty, which, once fixed in the mind, is a joy forever."2 The water in the gorge below the middle fall is deep and clear, although it boils and roars and is churned into foam as it comes from the upper falls. Then it plunges over the third and lowest fall into a pool of great depth in a circular basin, the sandy bottom of which may be clearly seen through the water. So swiftly does the current shoot into this pool that none but strong swimmers venture into its depths. On the ledges at the foot of this flume there is a "pot-hole" or a cup-shaped hollow, symmetrically gouged out of the solid rock in all almost perfect circle of perhaps two feet in depth and three feet in diameter. This is always partly full of water and we call it the Devil's wash-basin. Such pot-holes are familiar enough to geologists. The bed of the Connecticut River has many of them. Not the most uninteresting part of Sabbaday Falls is the upper fall. Originally the water flowed over the edge of a flat shelf of granite. Inch by inch, however, the flowing water has worn away the granite, cutting a polished channel back into the solid rock, until now the shelf has been eaten into a dozen feet or more. Hence, the water of this upper fall, instead of dropping perpendicularly as it did originally, now flows down a comparatively sloping incline. But the most picturesque part of the triple falls of Sabbaday is the middle fall. Under the flat shelf over which the fall first leaps there is a long, shallow cavern, perhaps eighteen or twenty inches in height. This depression extends in a horizontal semicircle above the rim of the punch-bowl, concerning which we are about to speak. Men have wormed their way along on this cut under shelf until, reaching the spot where the water pours over, they have endeavored to pierce the liquid column with their fist. So powerfully does the water rush here that only the strongest can thrust the arm through the liquid veil. Then there is the punch-bowl. This is a smoothly polished basin of pinkish granite, hollowed out like a bowl, perhaps five feet in diameter. In this basin the water whirls and twists around in such a way as to form a curl not unlike the one on a "kewpie's head," and then it leaps into the abyss with a roar. Sometimes, after a storm, the curl assumes the form of a face. This we have christened "The Spirit of the Falls." The perpendicular walls of this wonderful chasm are always wet and almost painfully cold. The moss, with which the face of the precipice is covered, retains the moisture and lets it trickle down incessantly over the perpendicular ledge. One bright summer morning, while my father and I were working over near Camp Comfort, at the edge of the woods near the Mast Road, a child came running towards us shouting at the top of her shrill voice. We hurried to our cottage where we learned that M―, who had brought up two friends to camp near the falls, had just run through the Valley shouting, W― has shot himself at the falls!" The two older Smith boys, starting off on the run, already had disappeared in the direction of the falls. My father made a stretcher by sawing off the legs of a canvas cot, gathered up a roll of cheesecloth for bandage, and started after them. He met the party a few rods from the falls. The brother of the injured man had torn his clothes into strips to bind the wound and make cross-straps for a rude stretcher of poles. Quickly the wound was re-bandaged with cheesecloth and the sufferer transferred to the more comfortable stretcher. While the victim was being brought down the old Indian path, M― raced down the town road for a horse and wagon. Meeting a native who was comfortably jogging along in his "hahnsum kerridge,"3 M― breathlessly explained the predicament of his friend, but had considerable difficulty in convincing the owner that the need was urgent. He must first "bait his horse," he argued. But M― was insistent and had his way. Just as the extemporized ambulance reached the woods, the party appeared. W―, though chalky-faced, weak from loss of blood, and suffering agonies from the tourniquet, was game to the core and did not permit a murmur to escape him. At the hotel a bedspring was secured and the wounded man was transferred to the mail-wagon. Soon the sixteen miles were covered and the party dashed up to the Conway Station just in time for the afternoon train. That evening found the luckless camper in a Boston hospital, his wound properly dressed, his life and limb saved. Today he is as well and sound as ever and a stranger never would know how close a call he once had. The accident took place thus: The young men had been swimming in the pool at the foot of Sabbaday Falls, and were putting on their clothes again. W― wore a 44-caliber Colt revolver in a holster of very flexible leather. This holster swung against a rock, discharging the weapon. The bullet passed through the leg, just missing the bone. Evidently it hit a large blood-vessel, for he bled "like a butcher." Usually the pilgrimage to Sabbaday Falls is made on the visitor's first Sunday in the intervale. The very name suggests such a plan, and moreover the quiet, cool stroll makes an ideal "Sabbath Day's journey." Perhaps we may see a big buck jump up and bound away or we may find the hen-hawks "at home" on their nest. But even if we catch no glimpses of wildlife, the winding river, the singing brook, the great pipe-organ of the falls, the life-giving air and healing sunshine will amply reward us for our attendance at the falls church at Church's Falls on the Sabbaday. And within the sacred walls of such a sanctuary one's mind is filled with thoughts of Him who is Lord of the earth and heavens, who gives us mountain, brook and blue sky.4

_____________ 1. See Chapter on Albany.

|