|

Table of Contents

Next

Chapter

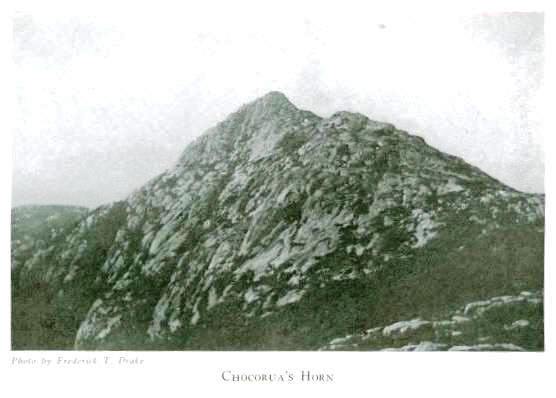

CHAPTER VII CHOCORUA'S HORN AND LEGEND Over the eastern shoulder of Paugus rises a sharp peak resembling a breaking wave.1 This, Chocorua's summit, is likened to various things. The most striking resemblances from our valley are first the horn effect, and secondly that of a sleeping Indian, with perfect features, feathers and shoulders. Drake says, "Mount Chocorua is probably the most striking and individual mountain of New England."2 It stands as the helmeted leader of the mighty troop behind it,―

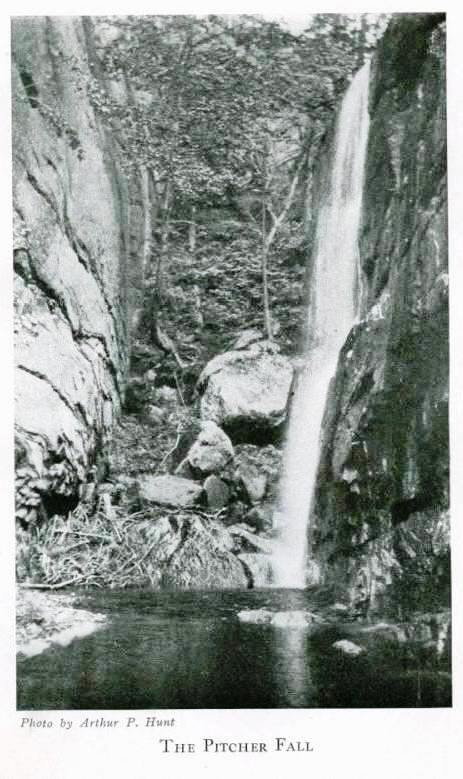

From different standpoints Chocorua presents entirely different shapes, causing Mr. Sweetser to remark: "The various aspects to the aesthetic observer may be seen from the following adjectives which Starr King applied, in different places, to this peak: defiant, jagged, gaunt and grisly, tired, haggard, rocky, desolate, craggy-peaked, ghost-like, crouching, proud, gallant, steel-hooded, rugged, torn, lonely, proud-peaked, solemn, haughty."4 This peak, with the exception of Mounts Adams and Washington, the sharpest of the entire system, is seen from afar―from the lake country and even from the border towns of Maine and New Hampshire.5 Chocorua is the first real mountain identified from the train by the traveler coming from Boston or the south, and being the most picturesque, is usually the last to be erased from the memory.6 The reason this "old horn" stands out so much more imposingly than its neighbors is not only because of its steepness and unique shape, but also because, far down on its granite sides it has been denuded of its forests. One dark night many years ago Chocoua lifted up a pyramid of flame. Concerning this picture Drake writes: "A brilliant circle of light, twenty miles in extent, surrounded the flaming peak like a halo; while underneath an immense tongue of forked flame licked the sides of the summit with devouring haste. . . . In the morning a few charred trunks, standing erect, were all that remained of the original forest. The rocks themselves bear witness to the intense heat which has either cracked them wide open, crumbled them in pieces, or divested them, like oysters, of their outer shell, all along the path of the conflagration."7 To this day the charred remains may still be seen, and now, because of this fire, scores of natives each summer make pilgrimages to this peak and return with their huge milk-pails filled with blueberries.8 To me the best way to enjoy a mountain, besides admiring it from a distance, is to climb it. Dr. Jackson is recorded as saying, "Those who wish for a laborious mountain excursion can ascend Chocorua Mountain from Albany."9 He might have added that, as it is the most laborious, it is also the most varied and interesting way of ascent. Several accounts have been written about the climbs up Chocorua and scores of other articles on the mountain itself have appeared. If one plans to scale "Chocorua's horn,"10 a day should be selected just after a storm, with not a cloud in the sky, and when every tree on the distant peaks may be clearly and distinctly seen. Such days usually are found in late August or in the autumn. The "Chocorua Trail" may be found just the other side of the Champney Brook, which gurgles musically east of the Frenchmen's houses at the lower end of the "Great Intervale," where said brook crosses the road, nearly four miles from "Shackford's." This part of the journey, therefore, may be made in an automobile. Upon reaching the Champney Brook we shoulder our baggage, and enter the woods on a well-worn logging-road, running alongside the brook, which it crosses and re-crosses. The tall grass and bushes lining this road are still very wet from the dew, and sparkle beautifully when an occasional flash of sunlight falls upon them. Just ahead there is a turn in the path. While rounding this bend a few summers ago, on returning from the climb, we saw a magnificent red fox glide swiftly across the road and head straight for the Frenchmen's chicken-houses. Later a confused squawking of hens announced the success of the raider. Upon entering the woods that day we had noticed a litter of pigs and several chickens in the clearing. Reynard, after gazing, covetously upon them, evidently had been unable to resist the temptation. Presently the ground becomes more irregular, and in places spring freshets have so gullied the road that a very "contrary sidewalk" (as tipsy Pat said) lies before us. Now and then a warm ray of sunlight pierces the cool, damp woods, and, falling upon us, cheers us into buoyant gladness. Now a little grass-covered clearing opens before us. Look at that grass! The one thing that can be raised to perfection in these cold regions is hay. The grass in this abandoned clearing is at least four feet high. A ruined lumber-camp lies in the clearing. Only a few years ago a French boss was housing his lumberjacks in this very camp, yet, during this short period, these temporary buildings have crumbled and soon will have entirely disappeared. Here a roof has caved in, there a whole building is prostrate; again the front, back, or side has fallen away, leaving the once inhabited structure now a tragic ruin of neglect and lonesomeness. About two years ago we discovered the cutest and most active little house-cats playing among these ruins. Evidently when the men left, these pets had either remained behind or returned. And now they were as wild as their much feared undomesticated relatives, the Canadian lynxes, although of diminutive and harmless size as compared with the pussies of the tasselled ears. Farther on our path plunges into a tall and ancient growth. This section of the trail is exceptionally beautiful, along soft, leaf-matted road, skirting the side of Paugus, and with a precipitous spur of Bald opposite; while at our feet lies the Champney valley. For a mile or more we pursue this course, rising higher and higher all the time. Once in a while, when a rift in the foliage permits, we look back and obtain fragmentary views of distant blue mountains. The silence is broken by the murmur and splashing of the brook. We push our way steadily onward, gaining elevation all the time. High above the brook-bed we are presently confronted by a "parting of the ways." To the right a road runs off, leading to the crest of the hill we are on. This is not our road. We must keep to the left, climbing over a long stretch of old corduroy road. So steep is the pitch of this hill, whose side we are slabbing, that, although the logs of the old corduroy road are firmly driven into the ground at the right, their left or outer ends have to be supported by timbers at least two feet high above the ground, to make the road-bed level. In many places these supports have rotted or been burned away, and the logs have either fallen down or been left projecting into the air. Onward still we go until the road brings us up to the brook over which lie the charred and rotted remains of a log bridge. Let us pause here. From below, at our left, rises the subdued roar of a small waterfall. A foot-path leaves the lumber-road, following down the side of the brook to the falls which we hear. In the early summer of 1915 a fire raged over Bald, the eastern shoulders of Paugus, and apparently was checked here, although on the opposite ridge it swept on for some distance. Hundreds of acres were burned over, and many magnificent trees succumbed to its flame. Hence with not a little care we must pick our way over and around charred stumps and logs, blackened boulders and red, leafless bushes. Now we stand on the large rock at the foot of the falls. This fall, called the Champney Fall, is a long thread of water, tumbling from ledges sixty to seventy feet in height and splashing loudly on the smooth broad rock at its base. Owing to the scarcity of water, especially since the fire, as its bed above is now unprotected from the sun, this stream is but a mere thread. During the spring freshets these falls are wonderful. A short distance to the east, and now in plain sight, is another, the Pitcher Fall, exhibiting rare delicacy of outline. Of this fall Professor Huntington, once the state geologist, said: "Not a dozen rods away, but almost hidden by the trees, we discover one of the most beautiful falls in New Hampshire. . . .The sunbeams fall aslant through the trees; the eye follows the high perpendicular ledge that runs at right angles to the stream, and through the leaves of the trees we can see the small stream where it comes over the ledge, then it falls down, striking the rock that projects just enough to throw the water in spray, and break, for an instant only, the continuity of the stream. In the entire fall there are three of these projections, where the water is thrown in spray, and after the continuous fall it rests in a great basin, where it flows out and runs into the stream we have followed."11 By many these falls are collectively known as the Champney Falls, but, in reality, the Champney and Pitcher are two different falls, one being located on the main brook, while the other is on a branch which flows into the Champney at this point. Having gazed upon these picturesque falls, we retrace our steps, up the steep foot-path, to the lumber-road once more. And a sharp little scramble it is, too. We are ready for a few minutes' breathing-time when we reach the road again. Here, where the lumber-road crosses the brook, we find ourselves in a cozy nook between the hills. At our very feet is a shady little pool surrounded by moss-covered ledges. This is known to us climbers as the "spring," although it is not properly a spring, but only a little basin into which the clear water flows from its rocky bed. Here we fill our canteens. One day, while returning alone from the summit of Chocorua, my father was suddenly greeted by the sight of a "bob-cat" at this very point. Happily the animal disappeared as quickly as he had appeared. Do you notice that smoothly polished rock at the edge of the pool? That particular rock used to be covered with moss―I remember it well. When a very little fellow, I was sitting on it one day when, presto! down I slid into the water. I was soaked to the skin and not until long after the sunshiny ledges had been gained was I dry and comfortable again. Roughly we estimate the "spring" as about halfway between the town road and Chocorua's peak, but more than half the work is still ahead of us. We have been comfortably jogging along so far, rising bit by bit, but now the real climb begins. We go through a short stretch of leafless, charred woods, and then an enormous open patch appears. We now see before us the northwestern face of Bald Mountain. Some years ago this area was stripped by the lumbermen, and, because of the impenetrable tangle of dead trees and branches, it is termed the "slashing." Here used to grow beautiful tall and straight trees, as noble trees as any in our range. Probably scores of King George's brigs and "seventy-fours" were indebted to such places as Chocorua's "Cathedral Woods" for its masts.12 After the mast-trade ceased, there came the lumberjack and the hurricane, and lastly, though not least, the fire. The road skirts the left side and runs above the area of devastation. Because of the steepness of this part of the climb, frequent rests are required, and, while resting, beautiful views may be had. The sun beats down in full force, but, upon our recalling the chill of the woods, Old Sol is quite welcome. High above us Bald's ledges glisten, and above them the fleecy clouds, floating in a pure blue sky, present such a picture as may never be seen in Chicago, New York, or any other city. Looking to the north and west, we see an innumerable company of mountains, like an immense herd of rolling blue elephants. Far below are emerald farms bespecked with houses, the town road, and the wriggling and meandering Swift River which plays hide-and-seek with the road. Perhaps the stillness is broken by a shrill whistle or cry, and, high above us, we see a magnificent eagle. There have been summers when from this spot we have repeatedly seen a pair of huge eagles, sometimes near, sometimes far away. As we rise higher, the mountain system unfolds itself. To the north and west, faint blue ridges are ever added to our view. Almost at our feet we see the precipitous spur of Bald. While descending at about this spot in the summer of 1915, we noticed two khaki-clad objects walking about amid the charred and red forest. On nearer view, they turned out to be two large deer. We watched them for a few minutes, until, taking fright, they bounded off and were lost to sight in the charred debris. Now a narrow patch of woods bars our approach to the ledges. It is soon traversed and we arrive at a curving ledge upon whose top we see a white sign board saying "PATH." From here on, our progress is guided by piles of stones, and formerly by spots of white paint also. As a ledge cannot be "blazed" with a hatchet, these little guide-posts have been erected by the Appalachians. We make our way forward, across slippery ledges, over patches of disintegrated rock, and sometimes along a tiny path closely fringed with blueberry bushes and occasional patches of dwarf trees. At length the lofty ridge between Paugus and Bald, which connects Chocorua with the latter, is gained. Last summer, shortly after dinner, we noticed that the sky had suddenly clouded over. As usual, we had eaten our lunches just over the eastern slope of the summit. We saw a storm rapidly approaching and pouring down in such sheets that already Passaconaway had been blotted out. Instead of crawling under the "Cow," or seeking out some sheltering ledge or cave, we dashed for this very ridge. For a thick stunted growth is here so closely matted together that, by crawling under it, one is almost rain-proof. No sooner had we made ourselves secure in this shelter than, with the fury of a mountain demon, the storm broke. Did it hail and pour? I never saw anything like it. A party of Appalachians, I think, returning by the Piper Trail, passed within fifty feet of us; we could hear their conversation plainly, yet they did not see us. They hurried by, tightly clutching their coat collars and struggling against the driving rain and gale. I need not say that even before the storm raged five minutes these luckless climbers were thoroughly drenched. Half an hour later, the sun again beat upon us and we left our cozy shelters, warm and dry. Looking east, towards Conway, we saw a beautiful triple rainbow, the left end of which seemed to rest in Walker's Pond, while the other was near the Madison station. All three bows were perfect in outline and coloring.

The few remaining rods are quickly crossed, and we stand upon the northern and lesser summit of Chocorua. From here a noble view may be had, much like that from the peak, except southward. Before us looms Chocorua, dark and forbidding, as if the weather had darkened it―like a battleship―to conceal it from its adversaries. Says Ward: "I know nothing more wildly beautiful or more unique in the White Mountains than this immense granite shaft which suddenly presents itself when, in the ascent, the crest of Bald is reached, or which seems to rise straight into the sky from the south. The appearance is more massive and more grand than when you see it from the level of the summits in the distance. Here it rises in front of you to a height of perhaps eight hundred feet almost straight into the air, without a tree, or hardly a bit of scrub, to relieve the weather-beaten granite cliffs, which are so steep that without the aid of man the peak would be almost unreachable. . . . I know not anywhere a cliff that rises sheer into the sky with such abruptness and massiveness as the chief peak of Chocorua which towers almost over your head when you are at the base of its principal elevation."13 I should advise all trampers and photographers wishing to take away with them adequate memories and pictures of Chocorua, that they fail not to view the peak from this northern spur. The views from the southern approach are not complete without this other. But this castellated promontory is not the summit. Our real conquest is still ahead of us. The main fortress must yet be stormed. We cross the ridge, descend into the little ravine, and soon reach the spring. This is marked by a white cross painted on a flat sheltering rock facing the north, overhanging the tiny pool below. Over massive blocks of granite, through crevasses and up cracks in rocks we scramble, and shortly reach a little circular path leading to the summit. At last, all breathless, we reach our goal. Here upon the very topmost rock―about as large as a good-sized dining-table14―we find a sixty-foot flag-pole, firmly guyed to the rocks, and from which on exceptionally calm days float the "Stars and Stripes." The fire warden, residing in a tiny camp on the southwest side, is the "color guard." Also a circular stand is attached to this peak. The pole and stand were recently erected. The circular stand formerly held a map which included all the country visible from Chocorua―of inestimable value to the tourist. Whether the wind or some human vandal removed this map I know not, but it is no longer there. One of the best views in the entire White Mountains may be enjoyed from Chocorua. Many descriptions of the skyline have been written. Those who make the ascent will find the following account from Osgood comprehensive and accurate:―"On the west, below and adjoining Chocorua, are the ledges on Paugus, whose top is nearly level, and has no peak. Over its right side is the dark and prominent Passaconaway, falling off sharply on the right; and over its long southern flank, across the upper clearings of Sandwich, is Mt. Israel, rising behind the low cone of Young Mt., Mt. Wonalancet being in the foreground, south of Paugus. On the right of Israel, and much higher, is the dark mass of Sandwich Dome. Whiteface is nearly west, on the left of and adjoining Passaconaway. On the right of and beyond Passaconaway is the long and many-headed ridge of Tripyramid, beyond which are the sharp peaks of Tecumseh and Osceola, the latter being seen on the left of the white mound of Potash, which is below in the Swift River Valley. Much farther away in this direction (west by north) is the high plateau of Moosilauke, over the Blue Ridge. About northwest, towards Mt. Hancock, is the square-topped mass of Green's Cliff; and the high spires of the Franconia Range rise on the distant horizon, with the gray sierra of Lafayette most conspicuous. On the right of Hancock is the imposing pile of Mt. Carrigain, looming up boldly out of the Pemigewasset Forest; and on its eastern side is the sharply cut and profound gorge of the Carrigain Notch, through which a part of Mount Bond range is seen. Close on the right of the Carrigain Notch is the remarkably pointed peak of Mt. Lowell, flanked on the right by Mts. Anderson and Nancy, on the same ridge. Under this range is Tremont, with its highest point between Anderson and Nancy; and Mt. Hale appears over Anderson. On the right of Tremont, and near it, is the sharp crest of Bartlett Haystack; and between and far beyond Tremont and Haystack are Mts. Willey and Field. The purple cliffs of Mt. Willard are over the crest of Haystack, in the White Mt. Notch, through which a part of Mt. Deception is seen. "About north-northwest, six miles distant across the Swift River Valley, is the long ridge of Bear Mt., covered with woods, and on the right of Haystack. Between Haystack and Bear are seen the richly colored stripes on the side of Mt. Webster. Farther to the right, over Bear, is Mt. Clinton, below which is the red crest of Crawford, with Resolution and Giant's Stairs on its right. Mt. Pleasant is over the right of Bear showing a round and dome-like crest, beyond and above which are Franklin and Monroe, west-of-north of Chocorua. The houses on Mt. Washington are about north, between Mts. Parker and Langdon, beyond the Saco, and Bear and Table Mts., north of the Swift River. Table is the mountain on the right of Bear, in the same ridge, and Iron Mt. is over its flank. Above Iron is the deep cleft of the Pinkham Notch, through which Mt. Madison is seen. On the right of and adjoining Table is the long imposing ridge of Moat Mt., over whose northern peak are the crests of Thorn Mt. and Double-Head, with Baldface lifting its white ledges beyond. The pyramid of Kearsarge rises above the southern peak of Moat, and is marked by a house; and the rocky mounds of the Eagle Ledge and the Albany Haystack are across the Swift River, toward the southern peak. To the right of and south of Kearsarge are Blackcap, Middle Mt., and others of the Green Hills of Conway, with the clearings of North Fryeburg and Lovell visible through their gaps. "The character of the view now changes from a tumultuously upheaved land of mountains to populous plains, dotted with hamlets and ponds, and diversified here and there by low ridges. The white Conway road runs north along the base of Chocorua, curving away from its formidable rocky flanks and lined with farms. The beautiful meadows of the Saco emerge from behind Moat Mt., and pass away to the east in graceful bends. The fair village of Fryeburg is about fifteen miles east-northeast, on the left of and beyond which are the bright waters of Kezar, Upper Kezar, Upper Moose, and Long Ponds. Lovewell's Pond is close to Fryeburg, on the right. Nearer at hand is the bright hamlet of Conway Corner, at the confluence of the Swift and Saco rivers. Farther out in this direction is Mt. Pleasant, a long and rolling ridge which uplifts a white hotel near its centre. On the right of Conway, due east, is the broad mirror of Walker's Pond, over which are the Frost and Burnt-Meadow Mts., in Brownfield. Farther to the right, over Cragged Mt. and the hills of Hiram and Sebago, is the broad gleam of Sebago Lake. To the east-southeast the view passes over the Gline and Lyman Mts., and across the" counties of lowland Maine, to the city of Portland, at the gates of the sea. On a clear day a wide extent of the ocean can be seen in this direction, and extending away to the right. Farther to the right, over the adjacent Whitton Pond, are the distant hills of Cornish and Limington; and nearly southeast, over the hamlet of Madison, is Mt. Prospect, in Freedom. About one mile from Madison, and six miles from Chocorua, is the broad oval of Silver Lake, with the formless ridge of the Green Mt. in Effingham over it. The ampler sheet of Ossipee Lake is to the right of and beyond Silver Lake, and on its right, far out on the horizon, over the hills of North Wolfborough, is the crest of Copple Crown. "Chocorua Lake is close to the base of the mountain, on the south, with its gracefully curving sandy beaches, bordered with trees; and the white Chocorua Lake House is on the hill beyond, towards the hamlet of Tamworth Iron Works, with its tall-spired church. In the plain beyond are the hamlets of Tamworth Center, South Tamworth, and West Ossipee, and the White and Elliot Ponds. Then comes the long Ossipee Range, filling the horizon from south to south-southwest, with the ledgy sides of the Whittier Peak, below South Tamworth. The twin Belknap peaks peer over the Ossipee Mts. and are clearly seen. On the right of the range are portions of Moultonborough Bay, Lake Winnepesaukee, and Northwest Bay, studded with islets and divided by peninsulas. The Bearcamp and Red-Hill Ponds are next seen, with the hamlet of Sandwich Lower Corner, beyond which rises the double swell of Red Hill. About southwest, over the white village of Centre Sandwich, is the exquisite beauty of Squam Lake, with its blue bosom dotted with wooded islands. The sharp crest of Kearsarge is over its left part; the Bridgewater Hills are over the centre; and Mt. Prospect, near Plymouth, is farther to the right."15 On the verge of the eastern slope of Chocorua is an approximately cubical rock which is called the "Cow." It rests upon a narrow, saucer-shaped shelf. Under it there is a space several feet long and about a foot and a half high, which has sheltered many a traveler during the wild mountain storms.16 I have tried in vain to discover its resemblance to a cow. I do not know why a rock of this shape should be called a, "cow." It looks more like a liberty-cap than a cow, and if I were naming it, I should call it "Liberty Cap." Such a name, too, would commemorate the one who made a trail up here and first tried the experiment of maintaining a "Peak House," later carried on so successfully by Mr. Knowles. This pioneer was "Jim" Liberty, better known as "Dutch" Liberty, concerning whom I shall have more to say later. After drinking in the wonderful view, let us eat our dinner near the Cow, where we are protected from the strong northwest winds by the summit. Here, amid blueberries and sunshine, we may turn our attention to an entirely different feature of this mountain―the feature without which no mountain is really complete―its history, or, at least its thrilling legend. Chocorua was a real Indian. An old settler of Tamworth, Joseph Gilman, often used to converse with an older pioneer who had been on intimate terms with the Indian.17 There are several entirely different versions of the Chocorua legend, all agreeing, however, on the chieftain's death here. The Albany records have burned, so that nothing may be learned from that source. But I will give the legend in the forms in which it usually appears. It has been said that Whittier deemed the legend too sad to put into verse.18 Perhaps the commonest version is that given by Lydia Maria Child, as follows:―"At a late period in the history of the Indians around Conway and Albany, Chocorua was among the few remaining red men. His son, nine or ten years old, became intimate with the family of Cornelius Campbell, a Scot who had fled from the wrath of the Stuarts. One day the little Indian lad swallowed some poison, which Campbell had scattered about his cabin to kill a troublesome fox, and went home to his father to die. Chocorua, perhaps naturally, blamed Campbell, and, during the absence of the latter, he murdered the Scot's family. The Albany settler tracked the Indian to the summit of the present Mount Chocorua and called upon the fugitive either to throw himself into the abyss below or be shot. To this Chocorua made reply: "'The Great Spirit gave life to Chocorua and Chocorua will not throw it away at the command of the white man.' 'Then hear the Great Spirit speak in the white man's thunder!' exclaimed Cornelius Campbell. . . . Chocorua, though fierce and fearless as a panther, had never overcome his dread of fire-arms. He placed his hands upon his ears, to shut out the stunning report; the next moment the blood bubbled from his neck, and he reeled fearfully on the edge of the precipice. But he recovered himself, and, raising himself on his hand, he spoke in a loud voice, that grew more terrific as its huskiness increased, 'A curse upon ye, white men! May the Great Spirit curse ye when he speaks in the clouds, and his words are fire! Chocorua had a son, and ye killed him while the sky looked bright! Lightning blast your crops! Winds and fire destroy your dwellings! The Evil Spirit breathe death upon your cattle! Your graves lie in the war path of the Indian! Panthers howl and wolves fatten upon your bones! Chocorua goes to the Great Spirit,―but his curse stays with the white man!"19 Drake's version of the legend makes Chocorua defiantly spring from the rock into the unfathomable abyss below, before the appalled hunter can fire a shot.20 For years after, as will be shown in another chapter, the country seemed to have fallen under this curse. A second legend, very similar to the first, describes Chocorua as a chief of the Ossipees, who loved his native land too well to leave it. With a small band he held this mountain as an observation post. Here rangers, in quest of the bounty for scalps offered by the Massachusetts Government, destroyed his band and pursued their chief to the summit, where he pleaded his friendliness to the English and offered himself as prisoner. But the blood-money was too tempting and the white men were inexorable. Chocorua, flinging forth his terrible curse, leaped from the dizzy height. A third tradition, in all probability less authentic than the others, says that in 1761, long after Lovewell's Fight, when the power of the Pequawkets had been broken and they, together with the Ossipees, had fled to Saint Francis in Canada, Chocoma returned, seeking revenge, and was shot on this mountain.21 Charles J. Fox has embodied the legend in verse, as follows:―

It was "Jim" Liberty who made the pioneer experiment of running a hotel high up in the sky, on the shoulder of Chocorua. Later the "Chocorua Peak House" was purchased by Mr. David Knowles.23 Once, when spending a memorable night at the Peak House, I saw the venerable Liberty, who at that time was doing some work for Mr. Knowles. Liberty built a good carriage-road to his Half-way House. From that point, the trip to the Peak House was made afoot or on horseback. The old Frenchman, in guiding parties from the Peak House up to the summit (for the Peak House is not on the very top of the mountain but at the base of its conical rock apex), used to go barefoot in order to secure a firm foothold upon the slippery ledges. He would tie ropes around the timid and weak ones, to assist them over the most dangerous places in the trail. A clipping from an old newspaper gives us a graphic picture of, "Jim" Liberty: "It was at the old Half-way House, a little pine board shack in the heart of the black growth that binds with a grasp like iron the belt of Chocorua, most picturesque of mountains in the White Hills. "Mrs. Liberty laid aside her dish towel and came out and stood on the steps. "'Be this your first visit up Chocoruay?' she asked pleasantly. 'Well, you all must come in an' rest yerselves. Mountain climbin' ain't so easy as it looks, leastways Chocoruay ain't―won't you all have a drink of water? You be the first folks so far this mornin', but ain't a day we don't have near fifty, an' sometimes more'n that. They comes from all parts. You all will see 'em comin' by an' by. Be you goin' clear to th' peak?' She put a stick of silver birch on the fire. 'Wall, now, but you got a fine day for it. I guess it be right smart windy up along the peak, but all the folks who come around here says they wouldn't miss Chocoruay, not for nothin'.' "The little white-haire'd old woman sat down by the window and folded her hands. How the wind whistling through the cracks in the boards brought with it sweet odor of the pines. A mountain stream, water clear as dew and white and cold as frost, ran away from the house towards the far-away lake, Chocorua Lake. . . . "Straight from the back door of the Half-way House up the mountain side, until it was lost in the trees, wound the trail, the 'Liberty Trail.' "'You'll find it muddy to-day, I guess,' went on the old lady, 'in parts; but, law; it's all kind of ways goin' up a mountain, some mud, some corduroy, some harricane, an' some rocks-good many rocks, but Liberty an' me, we keep it up pretty well; ain't no complainin', an' it wa'nt easy. How long 'I been here? Well, I ain't been here only since I merried Liberty, but he's been here goin' on more'n thirty years, an' long 'fore that he made the road up Chocoruay. Lonely? Wall, a lots o' city folks here in summer time, you know, an' long after till the last of October, but then by the time winter shets in thar's never a livin' soul, 'cept maybe a party comin' fer lumber oncet in a while. But I ain't complainin'. I says to myself: "God give me good health an' a roofter cover me, an' He put me down here on Chocoruay Mountain, an' here I am ter stay." Here comes Liberty now. I guess he'll put up your teams.' "Dutch Liberty is a little old man 'going on nigh seventy-five.' 'I look after ze teams―for pay,' said he, pushing back his slouch hat from his bristling gray eyebrows, 'an' I haf to see zat ever one, he give his toll!' 'Dutch' Liberty is a French-Canadian, descended from one of the early coureurs de bois, so many of whom made up the first explorers of New Hampshire, as well as the great Northwest. Liberty is called Dutch by his Yankee brethren because his English is so lame and halting, and up here any kind of broken English or incomprehensible temperament is called Dutch. Then, too, there was another reason. After Liberty first opened his trail up Mount Chocorua, he placed a signboard on one of the blazed trees with a hand roughly drawn in charcoal inscribed: 'Dot vay,' and 'that be Dutch,' folks around here said, 'so Liberty be a Dutchman.' He is, however, in his disposition to exact his dues, true-bred Yankee. . . . "'Which ever ze way you go,' observed Dutch Liberty, 'be he to ze right or be he to ze lef', you weesh to God you took ze other, so ees he not all ze same thing?'"24 Let us take the precipitous path down to Mr. Knowles' Peak House, for it would be a great pity to leave the mountain without visiting this unique hostelry in sky-land. Picking our way downward, by the help of an occasional railing, and here and there a short flight of stairs, we catch glimpses of the house. Upon closer observation we see steel cables running over the roof and anchoring it to, the rock. On the night when our tent blew down, and when the Passaconaway House barn door blew-off, all of these cables except one snapped. Had that gone―! Not long ago Mr. Knowles built a large addition, a one-story dining-hall, which he thought it would be unnecessary to cable down. The following winter, I think, he spent abroad, and, upon returning, found his dining-hall scattered allover the eastern side of the mountain. Our delighted eyes are greeted with gorgeous sunset views over the western mountains and the lake country. Some people prefer to view the sunset from the peak but that necessitates a descent in semi-darkness, which is not pleasant and is somewhat dangerous. I recall a lover of sunset scenes who, some years ago, under great difficulties, was satisfying his desire. A horse brought him up from the lower world to the Peak House. This man was a cripple, the unfortunate victim of some trouble necessitating the continual use of crutches. Shortly before six o'clock he disappeared, and all search was fruitless; but after seven o'clock we saw him, in the fast waning light, swinging himself down from ledge to ledge as he came from the summit, a very difficult feat for an able-bodied man in broad daylight. Let me recall a night in the Peak House. The roaring wind, which fairly rocks our mountain shelter, causes the carpet to roll in waves like billows on a storm-lashed sea. We gladly respond to the supper bell, and with zest devour steak and potatoes and Mr. Knowles' far-famed hot blueberry pie. Soon darkness envelopes the house. We study the twinkling lights of far-off Portland for a time, then, wearied with our climb, we retire and speedily fall asleep. Next morning before four o'clock the bright tints of the eastern sky prophesy the coming of a new day. Before five the gorgeous sun begins to come into view over Mount Pleasant, Maine. "Are we on the ocean?" we ask ourselves, for all beneath us is hidden in a white impenetrable curtain of cloud, above which the mountain peaks, here and there, appear as islands on a boiling sea. The entire earth seems to be passing through an all-encompassing flood, with only the lofty peaks unsubmerged. This scene is short-lived, for, no sooner has Old Sol come out in his dazzling brightness than the clouds rise in perpendicular columns and presently vanish in the thin air. While beholding this scene one exclaims, "Transported with the view, I am lost in wonder and praise."25 At half-past seven the breakfast bell again welcomes us to the dining-room. We enjoy our meal of ham and eggs, after which we select some mountain post cards, and souvenirs made by the Bartlett Indians, which mine host keeps on sale. Then, shouldering our packs, we bid adieu to the picturesque "Knowles' Knoll," and, in a couple of hours, say farewell to Mount Chocorua itself until another summer, in our hearts most cordially indorsing the sentiment of Mr. Whittier which he once expressed in a letter to the artist, J. Warren Tyng: "I sympathize with thee in thy love for the New Hampshire hills, and Chocorua is the most beautiful and striking of all."26 Since writing the foregoing description of a night on Chocorua, I have learned that the Peak House has been blown to pieces. It was on [Sunday] September 26, 1915, that the building was destroyed. The steel cables did not snap this time, but, in spite of these, the boards and beams were torn one from another and wafted out like straws over the valley. Happily the house was unoccupied at the time of its destruction. In all probability a new hotel will be erected without delay. The altitude of Mt. Chocorua is 3,508 feet.27

_____________ 1. Bolles: At the North of Bearcamp Water, 154.

|