|

Table of Contents

Maps

Index

CHAPTER XVI FORTY BELOW ZERO IN PASSACONAWAY-LAND C-O-N-W-A-Y! C-O-N-W-A-Y!" Then the red-faced conductor slammed the door and disappeared into the next car ahead. Enveloping ourselves in heavy sheepskin-lined coats, we snatched up our bags and made our way to the platform. Low clouds hung cold and leaden over Chocorua's snow-capped tooth and the gaunt, leafless forests at its foot. The little station was approaching. Never had I seen it so thronged and so busily humming with excitement as today. As the train stopped, the crowd surged down the platform and in the midst―almost suffocated―was a Jolly red-coated figure, a blue-hooded Santa Claus. My chum and I were the only passengers getting off at Conway, and we claimed as ours the trunk which banged down upon the waiting truck. We were met by a swarthy, thin-faced, muscular man bundled up in a heavy red sweater. It was the stage-driver, who, after exchanging greetings, repaired to the livery stable for his mail-coach. While waiting for our Jehu to reappear, we took off our shoes and encased our nether extremities in huge "felts" which we had brought with us, and which are the common winter foot-gear in this region. The next few minutes we stumped about the waiting-room of the station, clumsily thumping our heavy heels and toes. Didn't we feel foolish and awkward, though an elephant on roller-skates was graceful as compared to the way we felt, for it was the first time we had ever worn such foot-gear. Our first attempts to navigate in these heavy boots must certainly have been amusing to the farmers, lounging about in the station, but they courteously concealed their mirth from our eyes. A "Who-o-o-a" announced the return of our driver, so we loaded our baggage into the mail-pung. The driver of the tri-weekly mail-stage from Passaconaway to Conway is entrusted by the few inhabitants of the Albany lntervale with all their shopping errands. Hence, at Christmas-time, his function is that of an assistant Santa Claus. Fond parents smilingly had whispered mysterious secrets into his ear on his way down, and now, piled high in the pung, were dozens of presents, on top of all of which a girl's sled was strapped. We pushed our baggage in among the express parcels, and, finding a narrow valley between two small mountains of packages, we crawled into it and found ourselves on the second seat, where we bundled up in anticipation of the sixteen-mile ride up into the wintry sky. The driver had donned a shaggy bearskin coat, which bade defiance to the marrow-chilling nor'wester which was bearing down upon us. There was a thick crust on the eight inches of snow. The leaden heavens threatened to pour out their wintry wrath upon us at any moment. Gliding up the street on our way to the Conway post office, we passed dozens of merrily jingling sleighs. The people of the whole country-side seemed to be here, doing their Christmas shopping. After a few moments' halt at the post office, we proceeded to the store, where we found awaiting us our provisions, which we had ordered ahead. Then, all errands being finished, our horses turned their heads homeward and we two passengers settled down to the stern business of life.

Swiftly down the road we slipped, past the ruins of the chair-factory, past the ball-field, now mournfully draped in a white pall, and through the covered bridge over the Swift we plunged. On our right and ahead of us were the indistinct forms of Kearsarge, Moat and the far-off Presidential Range, while on our left was Chocorua, with its tiny, solitary Peak House at the base of its jagged horn. Along the snow-clad meadows and up to Potter's Farm we flew; just north of this farm we skidded around the corner, took the road to Passaconaway and plunged in among sweet-scented spruces, pines and hemlocks. The Passaconaway Road is the only highway leading to our little valley. It runs almost directly west, skirting the Swift River. Scarcely had we entered upon this road when a snowflake fell upon my shoulder, then another and another. Small, but hard and thick, no feathers these, they were more icy, and appeared like bird-shot. A few minutes only and we were buried in a hissing cloud of whirling, spinning and tumbling snow. Sometimes with bowed heads and sometimes with the side of our faces to the snow-laden gale, we bravely fronted the blizzard. These snow "pebbles," driving into our faces, cut and stung like knife-blades. After facing the keen air some four or five miles, we became ravenously hungry. Opening our lunch-boxes, I offered the driver a large, rosy-cheeked apple, which he accepted. I noticed that he did not seem to eat it very rapidly. On biting into another apple myself, I found it to be frozen as hard as a rock. We attempted a few pork chops. Evidently the cold. storage man had been at work, for they were frozen stiff. Only the boiled eggs and sandwiches were edible and they seemed somewhat ossified. Having satisfied our hunger, I reached for the bottle of hot coffee which I had carefully stowed away in my sheepskin coat. What was my surprise and disappointment to find that I pulled out only the neck and upper half of the bottle. The other half zealously encircled a solid core of coffee-ice still remaining in the huge pocket. We tucked away our lunches and settled down for the bitter reality of ten more miles. Let "T. R." talk about "the strenuous life" if he wishes. We certainly lived it that afternoon. We were tucked in so tightly that only with the greatest difficulty could we move, and we were forced to maintain this cramped position for four mortal hours in the face of a biting blizzard. For it was a blizzard, in good earnest. The swirling snow-clouds were so thick that we could not see fifty feet in any direction. Ascending the height at Colby Chase's house, we were greeted with a friendly "Hello" from an unseen figure. Then a merry farmer came out to get his mail, jocularly saying: "Snowed out, you be." "Why out?" "Because if you were in the house you'd be snowed in." Having enlightened us as to our status, he disappeared in the direction of the house, bearing the welcome newspapers and a letter or two. Over the roaring Swift we sped, through the "Half Way Bridge," and then past the Ham Farm at the foot of Spruce Hill. This hill is one of the hardest hills in the state for autoists and is the bane of our valley. It is a long uphill pull of a mile or more. In places where the road narrowed we could just make out the steep embankment, plunging dizzily down to the river far below. At the very top of Spruce Hill we reached the "Devil's Jump." I described it faithfully to my chum Bob―how, on a summer day, one can stand here and, looking across to the opposite bank of the river, behold a sheer precipice down which, with perfect ease, one might coast in a fry-pan, though to accomplish such a feat in safety none but his traditional Satanic Majesty would be able. Of course I had to tell Bob about the mistake I made when a tiny youngster. One year, when I was four years old, my parents were on their way up to enjoy their annual summering in Passaconaway-land. Reaching the top of Spruce Hill, we all got out of the mountain-wagon (for the automobile had not yet penetrated our wilderness in those days) to view the Devil's Jump. After gazing across at the frightful ledges, and peering down the steep incline to the river so far below us, my parents returned to the wagon, while I lingered. They called, I refused to come. They inquired the reason. "I want to see the Devil jump. When is the Devil going to jump?" was my reply. But all the scenic wonders at the Devil's Jump had to be taken on faith by Bob on this December day, for not a thing could be seen except blinding snow-swirls. Clouds of steam rose continuously from the bodies of the toiling horses as they pressed onward. "Hooooo! Hooo! Hu! Hooo!" suddenly shrieked something a few rods ahead. Coming, as it did, out of the depths of the wilderness, it sounded uncanny and almost supernatural. But the next instant the mystery was solved, for there leaped into view, about fifty feet below us and near the river bank, the locomotive of the lumber-train. With a great puffing, rattling and clanging, the train of perhaps thirty little logging-cars, loaded high with snow-covered logs, rushed into view. Almost as quickly as it had come, with a clanking and creaking and squeaking of brakes, it disappeared. Again the brownish-white snow curtain shut out the scenery, and we were once more alone amid a solitude of spinning, driving flakes.

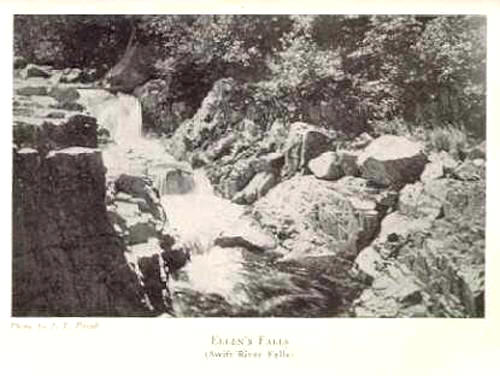

Mile after mile wriggled by under our runners, until finally, when within about five miles of our journey's end, we passed Ellen's Falls, or the Swift River Falls, as they ate sometimes called. Had it been a summer day, we should have jumped out of our conveyance and scrambled out over the level white ledges to the very brink of the falls. There a pretty sight greets one, for, as Sweetser says: "The river here plunges downward for a few feet through a series of boiling eddies, and is narrowed into a straight passage between regular and massive granite walls about twenty feet high and several rods long. The stream roars down through this contracted gorge, and overflows it during high water."1 But today, all blizzard-lashed as we are, we cannot tarry for sightseeing. Our driver urges on the horses and soon we reach the deserted houses once tenanted by French lumbermen; next the cheerful lights of the Annis house twinkle out; then we pass the store and Mrs. Colbath's. We are now speeding along on the home-stretch. In the darkness we leave behind the Loring bungalow and Jack Allen's last home. Presently the Hill Farm slips by, and now the hospitable lights of the Passaconaway House twinkle forth. Our long ride is ended and we are still alive. Here at the little hotel we find awaiting us light and warmth and a welcome from beloved neighbors. Without delay we are seated at a bountiful table and our plates are heaped high with steaming food. After supper we spent a pleasant hour in conversation. The genial postmaster showed us his stuffed lynx which had been shot a few months before. Several other "trophies of the chase," all taken in our intervale, were also in evidence, among them being deer-heads, a big hen hawk, and an owl, all beautifully mounted. Realizing that the sooner we got our cottage warmed up and the trunk unpacked the sooner we might go to bed, we regretfully bade our hosts "Good- night" and trudged across the road, knee-deep in snow, to "Score-o'Peaks." We had borrowed a lantern and a pail of water. We carried the trunk in from the porch, where the stage-driver had deposited it, and then lighted every oil-lamp in the house. With the thermometer registering eighteen below zero out of doors, needless to say we started a fire in "double quick" time, and in a few minutes the grateful glow of two red-hot stoves added to our cheer, and we discarded our heavy wraps as the frail summer-cottage warmed up. After unpacking the trunk, we next turned our attention to the making of the bed. There were two double beds in our chambers. We placed the two mattresses upon the bed in the room above the kitchen. Then spreading two pairs of blankets beneath, and four pairs on top of our woolen sheets, and laying several folded quilts at the foot of the bed, we contentedly gazed upon our handiwork, and then went down to get warm before turning in. We tucked away our provisions in convenient nooks and, drawing the table up as close to the stove as possible, we spread the remainder of our lunches upon it. Bob and I partook, with a relish, of toasted bread and hot malted milk. Among other edibles, a bottle of olives, hitherto unopened, "went the way of all the earth." Our lunches had been put up with the idea in view of lasting us three or four meals. Completing a most satisfactory lunch, we replaced in the box the half-frozen pork-chops, hard-boiled eggs, brittle sandwiches, and a mince pie which, in its present condition, would have made a good harrow roller-blade. Before retiring we nailed a thermometer to a piazza-post, placed the pail of water between the cook-stove and chimney, stuffed the stoves with huge chunks of wood and climbed the stairs. Upon Bob's suggestion, we brought upstairs our fur-lined caps. Full of joyful anticipation of the experiences which the future had in store, pulling our cap flaps well down over our faces, we soon were lost to the world, being transported to the "Land of the Mountaineer." "B-r-r-r, boom I" A snowslide, which sounded as if it would rip off the whole side of the roof, awakened us with a start. We pulled up over us all the quilts at the foot of the bed. We could almost see the cold. The wind was rattling the windows and doors, so that they sounded like the continuous chatter of Gatling guns. The constant roar of the wind told of the gale without and in such a racket sleep was out of the question. Chocorua stood out black and jagged over the broad tract of snow-capped hackmatacks. The cold had stopped our time-pieces. Bob remarked that the sun didn't rise so early here as in the Bay State and that it might be well to get breakfast before evening. So, after much hesitation, we counted a shivering "One, two, and―and―thre-eee." Before we had time to think better of our decision we were dressed in clothes, which felt as if they had lain on a sheet of ice for days. Talk about cold―frigid―there actually was ice in the bottom of our felts. For the next few minutes we hobbled about in frozen boots, but at length they thawed out and recovered their suppleness. Shivering and wringing our blue hands, we coaxed our smoldering fire into life and soon a flame shot up from the embers. The dismembered parts of our provision box, the only wood we now had inside the cottage, went into the stove, and leaving Bob as chef to pre- pare the breakfast I set out, shovel in hand, to excavate the summer wood-pile from the snow-drift. It was not yet broad daylight. Groping about in the semi-darkness, I began to realize how cold it was. Brisk exercise kept me perfectly comfortable, but how frosty the hackmatacks, how arctic the mountains, and how quiet and cold the intervale itself appeared! The sky gradually grew brighter and, as I was carrying in the last snow-caked armful of wood, Old Sol's welcome face appeared over Paugus. We placed the sticks behind and under the stove to dry and sat down to a hearty meal of steamed baked beans and coffee. Before the meal was over I noticed that the unconsumed beans were coated with white and that they had frozen solid while we were eating. The butter and the water in the pail were also frozen solid. Breakfast over, we soon had the dishes washed. Next we made the bed and swept the floor. Every time we opened our back door, which faces the west, the wind would send a shower of snow across the floor. This, as well as the snow which we tracked in, never melted during our entire stay. The wind had swept the sky clear of clouds, and the day was a perfect one. At short intervals, gusts of wind would come sweeping down from Mt. Hancock. We could follow the progress of these gusts as they swept over the mountains, for, from each peak as the wind struck it, a tiny cloud of snow would rise somewhat resembling the banner-cloud of the Matterhorn. Contrasted with the dark pines, the snow seemed even whiter and more glistening than I ever had seen it before. Passaconaway, whose snow-clad slide pierces its very heart, loomed up supreme. Then, too, the dark, bluish-green northern peaks formed a beautiful and restful background for the sparkling meadow in the foreground. The ledge-capped mountains, Tremont, Owl's Head, Potash, Bald, and Chocorua, were gorgeous, especially when the sun struck certain cliffs at just the right angle, making them scintillate like gems of the first magnitude. The long stretches of pine forest mantled with snow added the finishing touches to this wonderful picture, a sight never to be erased from one's memory. A day of such rare qualities must be made the most of. So, with rifle and compass, we started out for Allen's Ledge. When the ground is bare we can make this ledge in three-quarters of an hour. On the uncertain crust, however, we spent thirty minutes in crossing the field before even striking into the woods. In the woods, the walking was even worse. For a few steps the crust would bear us up, and then down we would go to a depth of a foot or two. The snow had covered all the bushes and completely obliterated the path. But, plunging into the woods at Camp Comfort, we started on the climb. It was not long before our heavy sheep-skin coats became uncomfortably heavy and hot. The toilsome ascent in the soft snow made us pant and we ate snow to cool off. After we had gone quite a distance, it seemed to me that we were too far to the westward. So we changed our course, going in a more easterly direction. This was a mistake. Had we continued but a few rods farther on our original course, we should have reached our goal. Instead of doing this, however, what we really did was to "slab" the side of Hedgehog ill a southeasterly direction. By and by, we saw, through the leafless trees, a high ridge above us. With fresh courage we dashed up the heights until we came out upon the top. Here, to our surprise, we found that, instead of being on Allen's Ledge, we were on top of Hedgehog, a mountain of respectable height―especially if climbed in a deep snow with "felts" on. One comes to appreciate the height of these summits after he actually has ascended them. We drank in the refreshing air, studied the view as best we could, and noted the abundance of fresh deer tracks all about. About noon we heard a distant yet clear jingling of sleigh-bells and, upon looking down into the Downes Brook Valley, we could see a road far below us, running parallel with the brook. We descended rather laboriously to this road. In going down-hill our "felts" went down easily enough, but pulling them out of the snow for the next step was a different proposition. At last we reached the "Downes Brook Tote Road." It was Sunday, but sleighs and pungs bobbed to and fro, and we met scores of pedestrians. Rounding a turn in the road, we came upon a few tar-paper shanties. The walls were of logs, locked together at the corners of the buildings. The doors, roofs, and in one or two cases the entire cabin, were covered with tarred paper. Leaves, dirt, and snow were banked tightly around the sills to keep out the wind. From a chimney made out of a nail-keg smoke curled upwards. From the fragrant odors issuing through the open door of this building we knew it must be the kitchen or cook-room of the camp. In front of several of the shanties were little groups of lumbermen, sitting on boxes, bags or overcoats, playing cards in the bright sunshine. A short distance down the road we turned around and took a picture of the camp, but only one cabin came out well in the photograph. We reached our piazza about three o'clock. The fire was quickly re-kindled and, putting the kettle, half full of ice, on the stove, we set the table. Bob had some baked beans and I, for a change, had half a dozen slices of bacon, slightly blackened by the hot fire. That evening we sat up long enough to get the two stoves red hot. Then, placing the water-pail between them and casting an anxious look at the mercury, we turned in. Dark clouds were skimming across the frigid sky and the wind had risen again. Remembering how cold it had been the night before, I placed the sleeping bag under the mountain of bed-clothes and crawled into it. The harder the wind blew and the more violently the little house shook, the more we enjoyed our adventure. We were tired after our day of trudging through the snow and soon fell asleep. Monday morning dawned intensely cold. A blizzard was raging, and nothing, not even the row of hackmatacks, close at hand, was visible. It was like being in a boat enveloped in a thick fog, for not even the white fields about us could be seen. The snow drove against our little cottage as if determined to penetrate its walls. We remained in bed until noon, when, "tired of resting," we mustered up our courage enough to jump out. The two fires were barely smoldering. The water-pail contained a solid piece of ice, and the thermometer affirmed that the temperature was fourteen below. Each cooked his own meal. Bob again dined on beans. I fried a good mess of onions. Each drank two cups of coffee. We played checkers awhile. Then Bob drew cartoons on postcards to send home by the next mail, while I sat by admiringly. About two o'clock a loud thumping and stamping on the porch announced a welcome visitor. In walked Tom S―, a congenial neighbor of our own age. This injected new life into our drooping spirits, and even if the wind did sift in through innumerable cracks, we managed, by hugging the stove, to have mighty good time and to keep a laugh from freezing. In the midst of our jollity we heard another pounding and in walked the postmaster, young Mr. P―. I tell you there is not everybody who is honored in the midst of a mountain blizzard with a call from a member of the Great and General Court of New Hampshire. What a good chat we had! All too soon, however, this congenial little party was broken up, for at dark, about half-past four, our companions left for their homes. About half-past six Bob and I sat down to our supper, a delicious meal of fried onions, chipped beef, deviled ham and coffee. Coffee was one thing we could make to perfection. Then, recalling the ancient saying that "a poor excuse is better than none," we set out for the hotel to "mail our letters." The warmth of the hotel was equal to that of Saturday night and we did hate to leave, a couple of hours later. Here we could take off our "mits" and have no fear of blue fingers. We listened to stories of the valley until our consciences told us that it was high time to return to the cottage. Although it was not so cold as on the previous night, we went to bed in the midst of a noise like that of bedlam. The windows, doors, and very roof creaked and rattled and seemed to be straining at every nail to free themselves from their iron fetters. The whistling of the cold wind and the straining of the house reminded me of the experience of the party which spent a winter on Mount Washington2 The members of that party found that the noise of the incessant wind became an almost unbearable strain upon the nerves. A warm, dazzling sun beating into our faces, woke us next morning. The sun was so 'welcome, the wind so still and the bed clothes so warm that we had nothing to rouse us from our perfect contentment. We just lay there, as Harry Lauder says, "doing nothin' and wasting our time." About half-past ten a thumping and pounding told us that "Jim" was there, but bed was too inviting. We watched him drive up the Old Mast Road and bring back to our piazza several sled-loads of wood, before we felt in duty bound to get up and greet him. Although not the perfect day of Sunday, yet it gladdened a pair of campers' hearts. The deep snow glittered, and every little while the wind would sweep it across the valley in a cloud and would rattle the snow against the house and windows like hail. All day long we could see the mountains flying their white flags. The mercury registered twenty-four below. We lost no time in piling up the wood which "Jim" had brought. While reaching above his head, Bob accidentally knocked down a package of butter. With a resounding thud it struck the floor. But the butter was so solidly frozen that the floor made no impression upon it. Whenever we needed butter for immediate use, we would cut off a corner by hammering a knife through the lump. On the eastern end of the porch, partially sheltered from the wind and blowing snow, we engaged in a shooting-match, spending a portion of the morning thus. The guns were scarcely cleaned and oiled when Tom put in an appearance. In the afternoon it commenced to snow hard again. Jim came over and regaled us with stories. The hours slipped away enjoyably, though not comfortably, for it was bitingly cold in spite of the two fires in the house. Jim left at dark, but Tom and I got to reminiscing, narrating anecdotes and swapping "Old Jack" stories. Loath to break up our conversation, Bob had volunteered to go over to the Passaconaway House for the mail and water. The mail goes and comes every Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday. Unfortunately he brought back news that we must return the next day. Under such conditions a bed seemed welcome, so after Tom left, at midnight, I retired. The mercury was see-sawing around the thirty-below mark and the wind seemed to penetrate to our very vitals. Bob had received several very interesting letters and remained a few minutes to read them. At length he came upstairs and had just put on his pajamas when I reminded him that he had not extinguished the lamp downstairs. Down he went, bare-footed, on the frosty stairs and floor, blew out the light and scampered upstairs ''as fast as two Jack-rabbits." For a long time I after I could hear him tossing and turning in an endeavor to warm his feet. Wednesday morning was as clear as a bell and cold―thirty-five degrees below zero tells the story! After a hot breakfast we packed the trunk. Then, taking the camera, we struck across the field to the lumber-railroad. On previous days we had seen the smoke of the engines as they plied back and forth, but, except in very few places, they were hidden from us by the huge banks the snow-plow had thrown up. In places we could walk easily, but just as we were about to think how fortunate we were, down we would go, the full length of our leg, and even then not reach the solid ground. In the fields the average depth of snow was at least four feet; while at the edge of the woods drifts about the pines and spruces were far higher than our heads. These little hills of sparkling white to the northwestward of every little tree presented a beautiful picture. Wherever it was possible we kept in the valleys or the hollow spaces between these snow-dunes, but often we were forced to cross a drift and that was a task long to be remembered, but not to be unnecessarily repeated. We would sink so deep at every step that it was all but impossible to extricate ourselves from the soft snow. Upon reaching the ridge made by the snow-plow we nearly came to a standstill. So soft and deep was this ridge that the more we struggled to force our way through it, the deeper we sank. Once or twice we fell down. Perseverance at length won and we stepped out upon the smooth road-bed. Locomotive "No. 2" stood before us, lazily steaming and smoking, a mere toy as compared with the huge locomotives such as whisk our "Twentieth Century" trains along; but for a dwarf, it is a powerful little kettle and strong and fast enough for this humpy little railroad. We took several snapshots of Tom's brother, the brakeman, the engine, and of each other perched on the unique logging cars. We followed the track for half a mile or more and then returned. The thermometer was taken down, we washed up for the first time since coming into the intervale, got into our city clothes, and, locking up, bade adieu to the dear little cottage, and waded over to the hotel for dinner. While we were dressing up, Fred Sawyer's pung, from Conway, swung into the hotel driveway. Because of our hasty departure we could procure no conveyance in the neighborhood and, therefore, had communicated with Mr. Sawyer by telephone. We all sat down to a piping hot dinner, served with a salad of stories. I recall only one of these stories. In substance it was as follows:―"Not long ago there came a couple of stormy days, followed by a holiday and a Sunday. After three days of loafing the lumberjacks sat back in their chairs and refused to work on Sunday. The boss, a little man, noted for his energy and efficiency, carne in and delivered an ultimatum to the effect that the company had been paying out large sums of money to feed them all the while they had been loafing, so that today, they must get out and work, even if it was the Sabbath. Several of the 'half-way' men went to work, but the others, great surly giants never left their places by the stove. The boss informed them that he would give them just five minutes to go to work. Not one of them had stirred when the fourth minute had passed, whereupon the little man procured from the storehouse a stick of dynamite and a piece of fuse. Placing these under the cabin and lighting the fuse, he informed the mutineers of their situation. In the wink of an eye the camp was emptied and with shouldered axes the recalcitrants hastened to their work. Calmly the boss stamped out the lighted fuse and put the dynamite back into the storehouse." After dinner we bade our generous hosts "Good-bye until next summer," and, bundling up warmly, were soon whisked down the road, round the turn, and the hotel was lost to view. I don't think I ever rode behind a finer pair of horses than on that downward trip. They kept up a steady, swift gait for the whole sixteen miles. Up-hill and down-hill and around curves we fairly flew. Now we were balancing at the Devil's Jump, as if pausing for a new start down the other side of Spruce Hill. At length the Ham Farm was reached and from here on we reeled off mile after mile of wriggling road. Yet none too quickly did we travel. So clear was it that almost every tree on the mountains was visible. But the cold was indescribably biting. My foot seemed to be asleep, and Bob's nose and chin were beginning to look chalky. By stamping my feet was able to revive them, and by continually clenching my mittened fists and driving them deep into my pockets I could keep them from stiffening. I noticed that my companion was this wonderful ride. Vainly did I try to point out Washington and several of the other noted peaks, but all to no avail; my chum would not even turn his stiff neck to view them. At length he remarked that all the information he desired was to know just how far we were from the station. At W. Colby Chase's we saw his cattle standing in four feet of snow, all huddled together and emitting clouds of steam. From Mr. Chase's we had a fine view of the Peak House, perched high up on the icy ridge which runs up into Chocorua's jagged tooth. Now we pounded and thumped our benumbed limbs and now, like tortured martyrs, we patiently endured the cold. If only we could have gotten out and walked for a stretch―but we had no time to lose if we were to catch the train for Boston. There never existed a more thankful pair than we were when we rounded Potter's Farm and pranced down the streets of Conway towards the station. Although the ride down from Passaconaway took only two hours, the ride up in the blizzard had been a negligible quantity compared with this cold. On the following morning the thermometers reached forty-six degrees below zero in the mountain region, and during our ride It must have been forty below. After entering the train we found Bob's face to be slightly frost-bitten. My heel did not get thawed out much before we reached Portsmouth. It is long after dark when our train pulls into the North Station, Boston. Once more we are home from the mountains. But how different has this trip been from those with which hitherto we have been familiar―our annual summer pilgrimages! And now, having returned in safety from our winter expedition of nineteen-hundred-and-almost-froze-to-death, let us bid adieu, until next July, to Passaconaway and to Passaconaway-land in the White Mountains.

_____________ 1. Osgood’s White Mountains, 342.

|