| Home

Boris

Sidis Archives

Table of Contents Next

Chapter

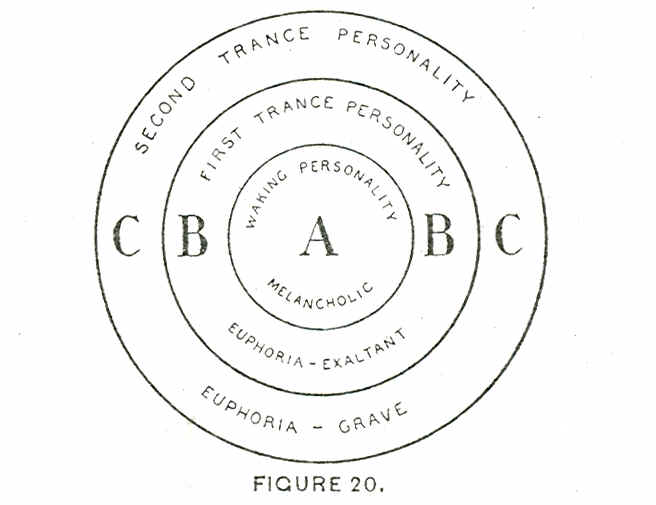

CHAPTER III THE PHENOMENA OF TRIPLE AFFECTIVE PERSONALITY IF now from the waking state, strongly tinged as it is with hypochondriacal melancholia, we turn to the patient's subconsciousness, we are confronted with a totally different state of things. No sooner did the patient pass into trance than a profound change suddenly swept over his whole being. A metamorphosis almost instantly took place in him. The intense misery of the melancholic state completely disappeared and instead of it a state of intense euphoria emerged. No greater change could possibly be conceived. The patient's face became radiant with happiness and lighted up with smiles; he could not utter a word without grinning and laughing with delight for the very joy of living. As far as affective states were concerned a new, totally different personality seemed to have emerged from the depths of the subconscious. In spite, however, of the profound change of the whole affective tone and of the emotional states the focal delusion persisted as much as ever and appeared to be far more definite in its outline, far better organized in its constitution. The affective state of depression was gone and an opposite state of well-being, appeared, and still the delusion remained in its full force. This clearly pointed to the fact that the delusion could well exist without the emotional melancholic state, and that either the state of depression was of secondary formation brought about by the gradual organization of the systematized delusion, or that the delusion, though being of secondary origin, had gained sufficient strength and independence to stand by itself, even when the emotional basis of depression was completely withdrawn. In any case, the fact remained that, notwithstanding the change of the affective and emotional states to their very opposite and contrasting conditions, the delusion remained as firm as ever. The trance personality, happy, contented, though still delusional, as far as the general mental state was concerned, approximated more closely to the patient's normal self before the mental trouble set in than the highly hypochondriacal waking self. Although there was such a profound change in the emotion of the trance personality, as contrasted with the waking condition, there was absolutely no change in the content of memory. The trance and the waking state were bridged over. In his trance the patient could vividly remember all that had taken place in his waking life. On the other hand, in his waking state the patient could recollect all that had transpired during hypnosis, though this occurred not without some effort. The memory was rather indistinct and was far from being vivid, the recollection appearing more in the nature of dream memory, being vague and indistinct, and could only be made clear by fixation of the attention. Later on, when in one of his subconscious states, the patient passed into a still deeper trance, and to our great surprise the whole affective emotional tone of the trance state with which we have become familiarized vanished, and a new emotional personality emerged. The metamorphosis was a very marked one; the change from one personality to the other was radical. From being happy, smiling, gay, and full of inexpressible delight, the whole attitude changed to one of quiet, composed, and even of grave demeanor. Things were not accepted in that easygoing fashion, with smiles and laughter, but were rather taken seriously and earnestly. The change that passed over the patient's countenance in his passing from one stage of trance into another and deeper one was extremely interesting to watch. It seemed as if from the depths of subconscious mental life a new person with absolutely different qualities and characteristics came to the surface of consciousness. The transformation was striking, and this change was all the more wonderful as the whole process took place rapidly. Not the least trace of sadness and dejection was left. The whole attitude of the trance personality breathed a quiet, composed contentment. The contrast to the melancholic waking personality, full of unutterable misery. and the antithesis to the first trance personality, merry, easy-going, and full of unspeakable bliss, could not be more complete. If the change was great in the life of feeling and in the emotional expression and attitude, the modification in the function and content of memory was still greater. The last trance personality could remember clearly and distinctly all experiences of the first trance personality, and also those of the waking personality, but neither the waking nor the first trance personality knew anything of the second trance personality. There were thus three personalities, each with its own moods and emotional states, with its own content and function of memory, but with the same persistent and stably organized delusion. The waking personality was melancholic and mentally diseased, with a narrowed-down content of psychic material. The trance personalities were comparatively healthy and with a wider and deeper content of mental life, with a greater activity of psychic functions than the waking personality; each succeeding personality being wider and more comprehensive than the one that had preceded it.

As far as pure function of memory is concerned, the interrelation of the three personalities may be represented by a series of concentric circles, the two trance personalities being designated by B and C according to the order of their appearance. Designating the successive personalities by A, B, C,―A standing for the waking, B for the first and C for the second trance personality,―then their inter-relations are such that while C has access to A and B, B has access to A, but not to C. In respect to memory the phenomena follow the general law of personality interconnection: Out of a series of interconnected personalities the functions of reproduction and recognition are retained by the ones rich in' psychic content and lost by the ones the psychic content of which is poor and limited. Memory thus is proportional to the amount of retained psychic content; this usually follows in the order of the depth of the uncovered psychic strata. Personalities spontaneously formed at a deeper subconscious level are the most comprehensive and have the best memory. Amnesia runs parallel to the ascent of psychic states. On the affective and emotional side the gap between one personality and another was far greater than on the side of memory. The three personalities, the melancholic, the exalted, and the grave, stood out clear and distinct in their outlines. Each personality emerged with its own distinctive affective physiognomy, the one passing into its opposite, not by transitional stages, but by abrupt termination with the emergence of one of the sharply outlined personalities. The affective emotional traits and characteristics did not intermingle to form a complex whole, but kept distinct and separate in their synthetic quasi-personal unity. The waking personality and the first trance personality may be regarded as contrast personalities and may possibly be referred to the same fundamental relation of contrast effects, prevalent in mental life whether in the domain of sense or in that of emotion. Of the three personalities the waking is pathological, the first trance personality is exaltant though nearer to the normal, while the sedate, contented second trance personality approaches as nearly as possible to the patient's healthy condition. It is well here to point out the fact that these sharply defined personalities form by no means a unique phenomenon; their course runs closely parallel to the well-known circular insanities of which folie ą double forme may possibly be regarded as most closely resembling in type the present case. In the different forms of circular insanities we meet with just such contrasting states,―a state of depression, a state of exaltation, and an intermediary more or less normal condition. These states are of longer or shorter duration, varying differently in the order of succession with each individual case. The analogy of this case with the general course of melancholia may even be a closer one. It has been observed that in the course of melancholia, when the patient is on the way to recovery, before he returns to his fully normal, healthy state, a stage of slight exaltation is passed through, due no doubt to results of contrast effects. The three personalities in our case present parallel conditions and a similar order of succession to that observed in the course of typical melancholia. The succession of the three states or of the quasi-personalities was of the same order, namely, the melancholic, the exaltant, and the quiet,―the normal. In the fully normal individual a similar course of succession of contrasting emotional states is observed. When relieved from an intense state of grief or anxiety, we pass temporarily into a state of exaltation before we settle down into our previous normal state bearing the marks of the outlived experiences.

|