|

Home Boris Menu Galvanic Research Menu Laboratory Instruments Used Part II

I The purpose of our present study is to investigate the relation of emotions and physiological activities to galvanometric deflections. Our aim is to ascertain whether galvanometric deflections can invariably be correlated with psycho-physiological processes. We attempted to eliminate all errors and obviate objections incident to the carrying out of such delicate work and also to deal with the problem of causation. This communication should be regarded as a preliminary one; further research is in progress. In his study of the emotions Ch. Férér was the first to point out the presence of electrical changes under the influence of emotions and affective states in general. He regards the changes as the result of lowering of bodily resistance brought about by the emotions and their correlative physiological processes. R. Vigoroux followed up the subject by a study of clinical cases and referred the electrical changes found not to skin resistance, but to modifications of capillary circulation under the influence of emotions. In experimenting with the mirror-galvanometer Tarchanov found galvanometric perturbations due to emotions, affective states, sensations and ideas; in fact, according to him, all kinds of mental states bring about deflections of the galvanometer. He describes large deflections apparently caused by the slightest emotion and change of affective states and even by mere memory and representation of an emotion. In fact, according to Tarchanov, even such intellectual processes as calculation give rise to marked deflections of the mirror-galvanometer. As the result of experiments which have been repeated by us in the present research he came to the conclusion that the galvanic phenomena manifested were due to secretory changes of the skin. It is to be regretted that Tarchanov did not follow up his experiments as he had promised to do in his original paper. Many other investigators such as Stricker, Sommer, Muller, Veraguth and more recently Jung, have taken up the subject and have advanced different views and hypotheses as to the causation, physiological and physical, of the galvanic phenomena in relation to psychic activities. While Stricker in opposition to Tarchanov rejects the theory of skin-effects and variations of the activity and secretion of sudorific glands, but ascribes the galvanic phenomena to circulatory changes under the influence of mental slates, Sommer regards the phenomena more in the nature of an artefact. He thinks that the galvanic deflections are simply the result of variations of contact between skin and electrodes and that they are due to the movements of the hand, voluntary or involuntary, and to changes of pressure exerted on the electrodes. This is a very serious objection which must be overcome before we can establish any relation between mental processes and observed galvanometric perturbations. Recently Veraguth and after him Jung have devoted much of their time and energy to the study of the relation of mental states to galvanometric deflections. Veraguth confirms Tarchanov's results and terms the galvanic phenomena observed by him under the influence of emotions and of mental states in general, as 'the psycho-physical galvanic reflex.' Jung has been especially energetic in calling attention to the galvanic phenomena of emotional disturbances and has attempted to utilize them in the detection and analysis of suppressed systems and possibly also of dissociated subconscious mental states. Peterson and Ricksher, working in Jung's laboratory, have in their investigations, performed on normal and on insane !individuals, further corroborated the relation between galvanometric changes and mental states in general. Large galvanometric fluctuations were found by them to be correlated with sensory, emotional and ideational system-complexes. The galvanic perturbations due to ideo-sensory states are referred to the affective states or 'feeling tone,' which, according to Wundt's doctrine, widely accepted in Germany, are supposed to accompany all mental processes. The following table2 may possibly give some concrete idea of the magnitudes, as found by these observers, of the galvanometric deflections under the influence of mental states:

An inspection of the table shows that the magnitudes of deflections vary greatly among themselves without apparent corresponding variation of the stimuli. Our results differ from these as the sequel will show.

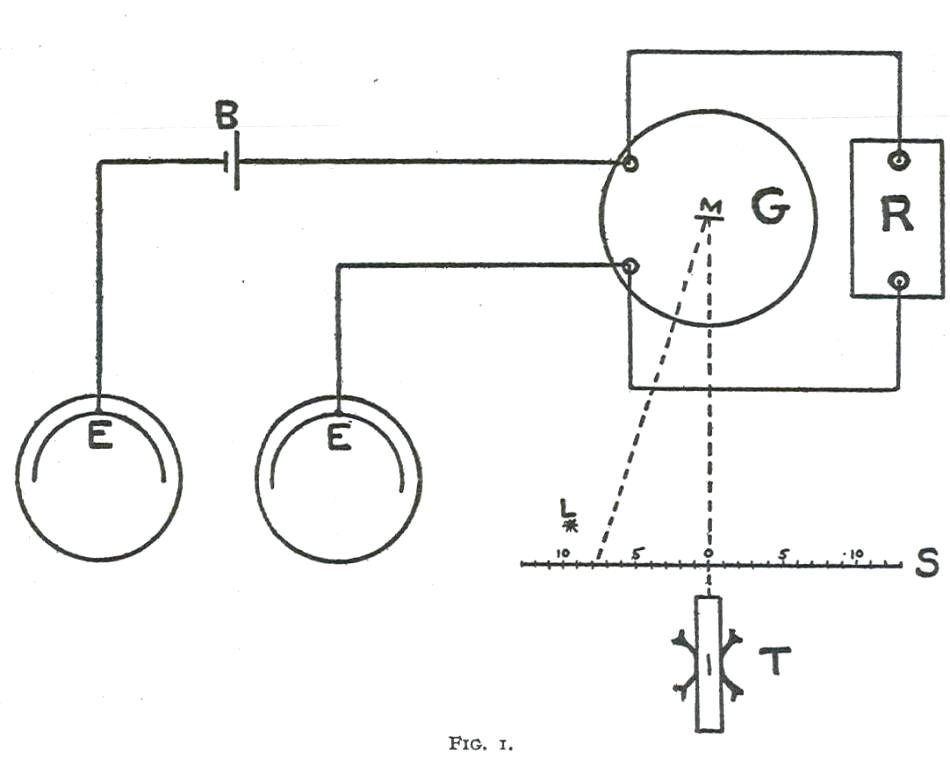

II The electrical circuit and apparatus employed by us for these experiments were as simple as possible, in order that there should be no doubt as to the origin of the effects observed. The arrangement was as indicated in Fig. 1.

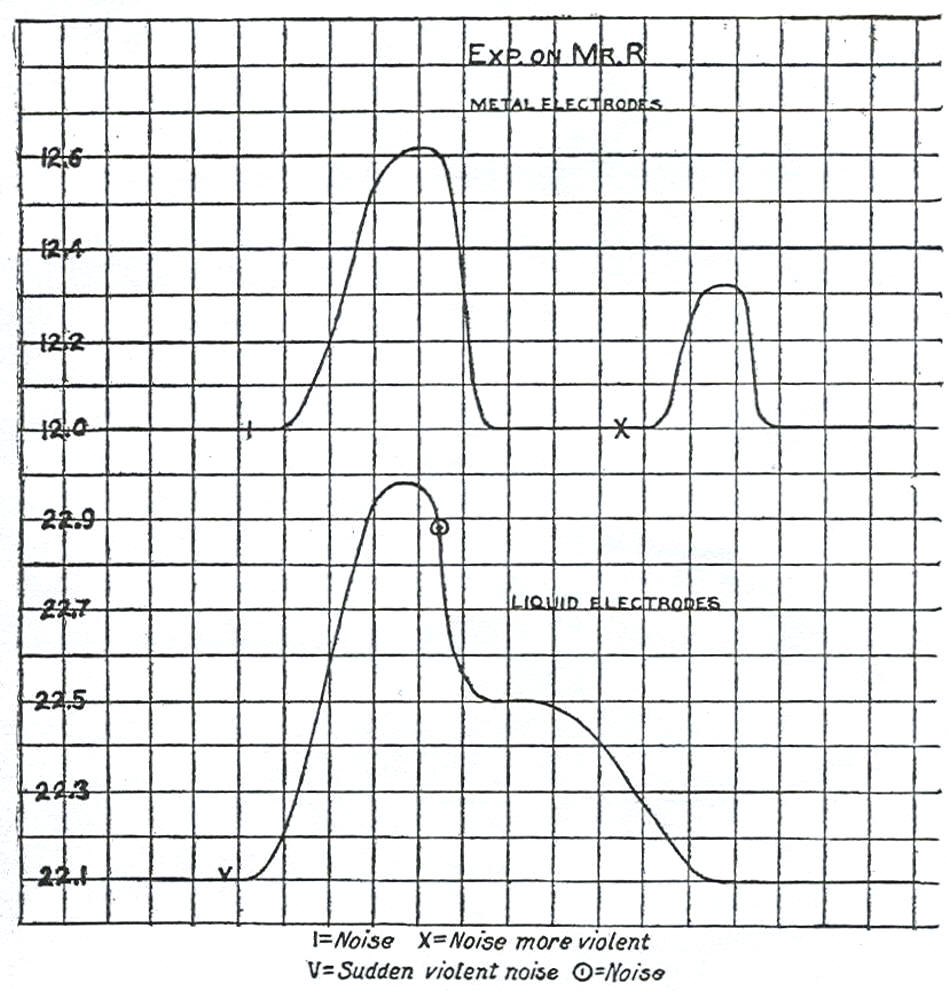

In series with a battery B was a sensitive galvanometer G and two electrodes EE, across which the subject placed himself, thus closing the circuit. The battery was a single cell giving a constant electromotive force of about 1 volt, which was sometimes replaced by a thermo-element giving only a few millivolts, and sometimes entirely removed from the circuit. The galvanometer was of the suspended coil, D'Arsonval type, and of extreme sensitiveness. The deflections were read by means of a beam of light deflected from a mirror M, attached to the moving coil of the instrument, to a telescope T with a scale S. A deflection of 1 cm. on the scale corresponded to less than 10-9 ampere through the instrument. This extreme sensitiveness was too great for many of our early experiments, so that a resistance R, which could be varied to reduce the sensitiveness to any desired degree, was shunted around the galvanometer. Not only is it important that the galvanometer employed should respond to very small changes in the current flowing through the circuit, but it must respond quickly, that is, without appreciable lag. The speed of reaction of the galvanometer was tested by direct experiment. First, with an all copper circuit, and then with the human body across the electrodes EE, the circuit was made and broken at the rate of 200 times per minute. Each change was definitely observed by corresponding galvanometric deflections. The electrodes EE were glass vessels of about 4 liters capacity, nearly filled with a strong electrolyte, as for instance a concentrated solution of NaCl. Into these vessels large copper electrodes C of about 500 cm2 area were permanently placed. The circuit was completed by placing the hands, feet, etc., one into each electrode solution. The galvanometric deflections may be due to changes in the resistance at the electrodes, brought about by such purely physical causes as motion or muscular contraction of the hand, stirring of the electrode fluid or similar incidental secondary effects. In order to eliminate the possibility of such effects it was necessary to devise such electrodes that the current through the circuit should within very wide limits be independent of the position of the hands. The possible sources of error at this point which would change the effective surface of the hand are twofold―(1) due to the variation of the liquid level at the wrist, and (2) due to movements of the hand as a whole. The following device was used to overcome these difficulties. The wrist was covered with shellac for a length of several inches, so that the free liquid surface of the electrode was always in contact with shellac. The shellac was covered by a layer of paraffin, though a moderate coating of shellac alone was such a good insulator that the electrode resistance became independent of the height of liquid on the wrist. In addition to this the hand was put in splints in such a manner that only a small fraction of the skin was covered, so that no appreciable muscular contraction of the phalanges could take place. Under these conditions the subject could move his hands about at will through a distance of several centimeters, stirring the electrode liquid violently―the equilibrium reading of the galvanometer remaining absolutely undisturbed. If now a stimulus was given which aroused an emotion or definite affective state of the subject, a marked galvanometric deflection was observed. A large series of experiments was performed under these conditions.

TABLE I

TABLE II

TABLE III

TABLE IV

TABLE V

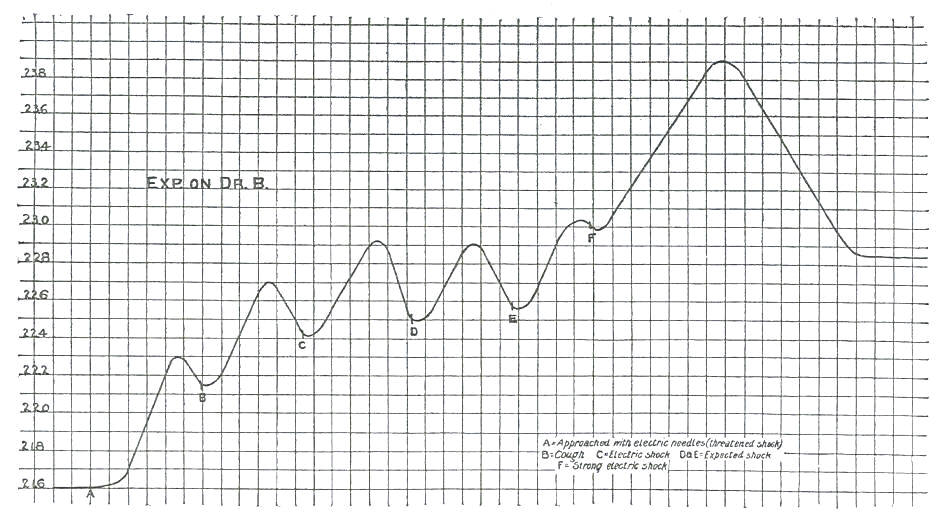

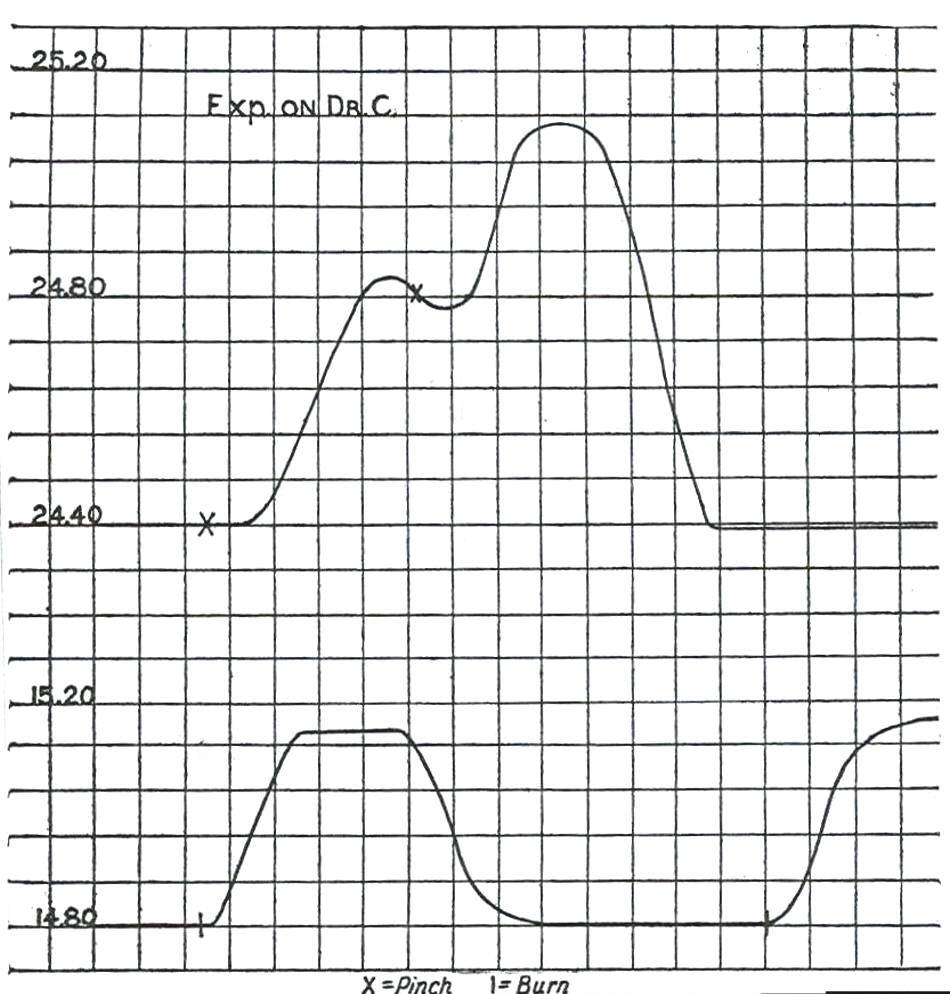

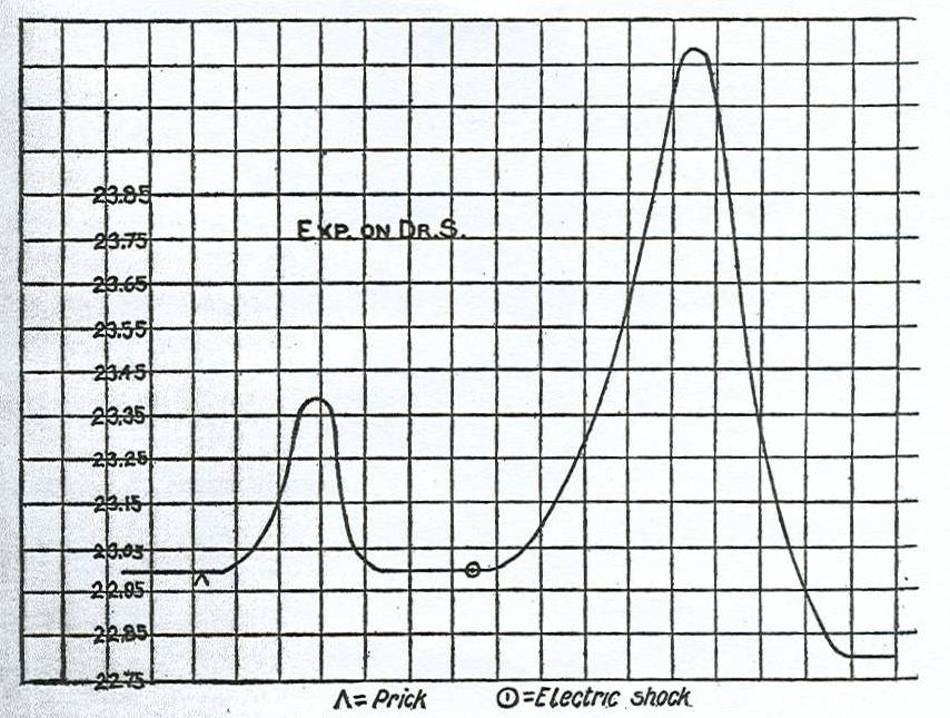

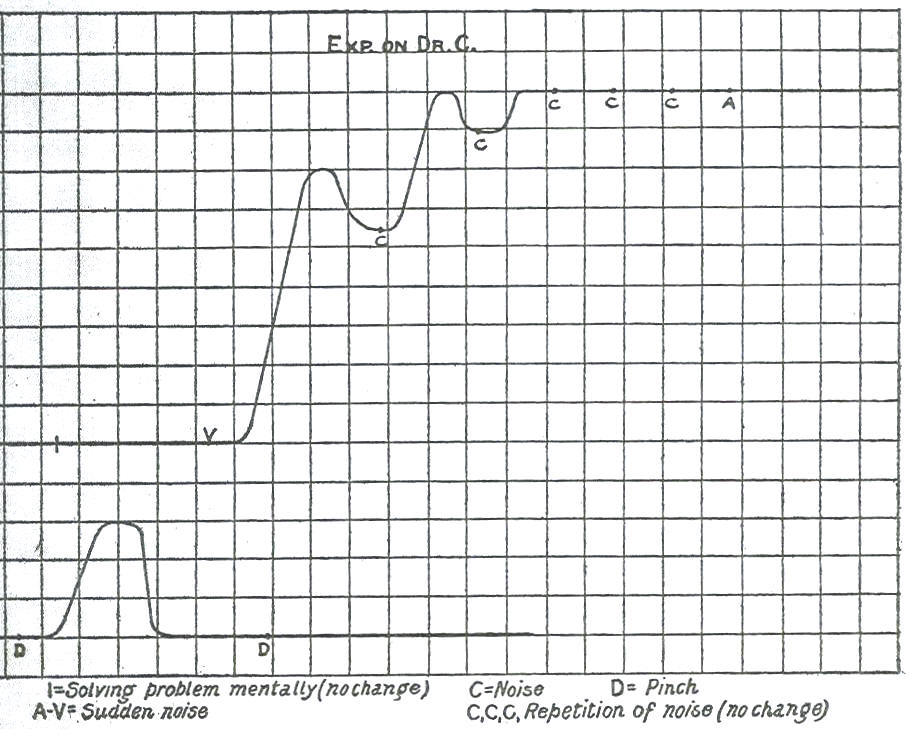

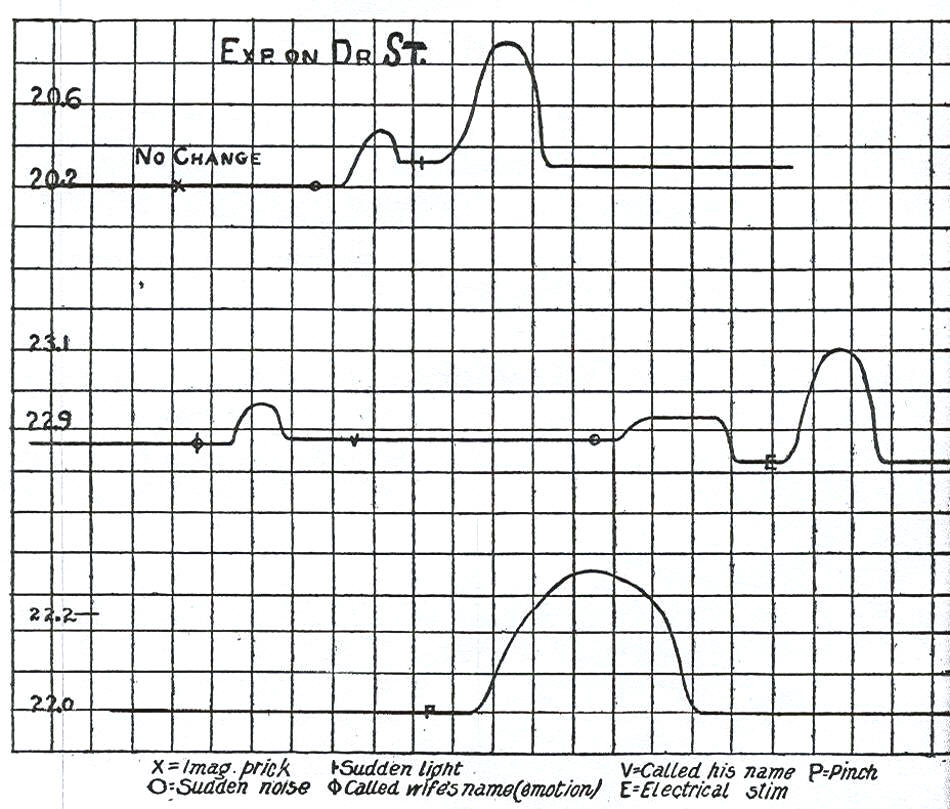

Plotting galvanometric deflections as ordinates and time as abscissć a series of curves is obtained. Out of a large number we have selected a few typical ones which show clearly the relative variations of galvanometric deflections under various conditions of stimulation. Where requisite we indicate in a short note the essential characteristic of each particular curve. An examination of the tables and curves shows that pure ideational processes such as thinking, calculation, solving problems, representing pleasant or painful experiences and even ćsthetic experiences such as looking at pictures have no effect, while sudden violent emotions and especially intense sensory stimulations of a painful or of a very disagreeable character, such as burns, pricks, pinches, electric shocks and unpleasant smells are followed by marked galvanometric deflections. The deflections diminish and finally disappear with the repetition of the same sensory stimulation.

It will be observed that there is a latent period between the time of stimulation and the beginning of the rise of the curve This latent time is somewhat variable, but is of the order magnitude of a few seconds. No attempt was made to study accurately such latent periods; the curves represent the magnitude of the deflection in terms of arbitrary time units. Particular attention will be paid to this point in a subsequent study.

It need hardly be pointed out that such definite variations cannot possibly be ascribed to changes in the circuit such as the introduction of thermo-electromotive forces, magnetic effects and the like; for these could scarcely time themselves to occur just at the instant of stimulation. For the sake of completeness of demonstration, however, a resistance box was introduced into the circuit across the electrodes EE in place of the human body. The reading remained steady to within one half millimeter for an indefinite time in spite of the jarring and disturbances which were purposely made more violent than during the experiments on the subjects.

Hence we conclude that the observed galvanometric changes do not take their origin in the physical part of the circuit, but are caused by physiological processes concomitant with the mental states aroused by the stimuli. We next pass to the study of the nature of these physiological processes.

_________ 2 Peterson and Jung, 'Psychophysical Investigations,' Brain, 1907. 3 All readings in this and subsequent tables are in centimeters. Horizontal lines indicate the end of the experiment.

|