|

Home Boris Menu Galvanic Research Menu Laboratory Instruments Used

The changes produced in the electrical resistance of the human body by various causes have been studied for many years but as yet no definite results have been reached. Ch. Féré was the first to report on the changes produced by emotions. In a communication made to the Société de Biologie in 1888 he noted that there was a lessening in the bodily resistance when various sensory stimuli were employed, and also that emotions caused the same decrease. R. Vigouroux had been working on the problem of electrical resistance in the human body with patients from the Salpétrière and had reached the conclusion that the old view that the resistance was due to the epidermis was wrong and that the condition of the superficial circulation was the real cause. He thought that variations in resistance were caused by an increased or decreased superficial circulation. Féré accepted these conclusions and added that "l'étude de la resistance électrique peut trouver une application dans les recherches des psycho-physiologues." Nothing new was reported for several years: A. Vigouroux in 1890 published a report on the study of electrical resistance in melancholies but added nothing; Tarchanoff, Stricher, Sommer and Veraguth have all published the work of the French investigators. The first real psychological researches with the galvanometer were made by Veraguth who worked with Jung's association experiments and this instrument in 1906. In 1906 work was begun in the Psychiatrical Clinic in Zürich to determine if possible the cause of the electrical resistance of the body and the various changes produced in it in normal and insane individuals by various stimuli. The apparatus used consisted of a circuit containing a single element of low E. M. F., a Deprez-d'Arsonval galvanometer of high sensibility, a shunt for lowering the oscillations of the mirror and two brass plates upon which the test-person places his hands and completes the circuit. The galvanometer reflects a beam of light to a celluloid scale to which is attached a movable slide with a visière, which, pushed by hand, follows the moving mirror-reflection. To the slide is attached a cord leading to a so-called ergograph writer which marks the movements of the slide by means of a pen-point on a kymograph-drum which is fitted with endless paper. For marking time a Jaquet chronograph was used and for the moment of stimulus an ordinary electrical marker. The problem of the cause of the resistance was first attacked and the results given are those obtained by Jung and Binswanger and as yet are unpublished. The resistance was found to vary greatly in different individuals with different conditions of the palmar epithelium. That the epidermis was the seat of resistance was proven by the fact that when the electrodes were placed under the skin the resistance was enormously decreased. This was done by piercing the skin of each arm with a surgical needle and using the needles as electrodes.1 The French investigators were unanimous in ascribing the changes in resistance to changes in the blood supply of a part caused by dilatation and contraction of the vessels, the greater the blood supply the lower the resistance and vice versa. That the blood supply was not a chief factor was proven by exsanguinating the part in contact with the plates with an Esmarch bandage when it was found that the galvanic phenomenon still existed. That the changes in resistance are not due to changes in contact, such as pressure on the electrodes is shown by the fact that when the hands are immersed in water which acts as a connection to the electrodes the changes in resistance still occur. Pressure and involuntary movements give an entirely different deflection than that which we are accustomed to obtain as the result of an affective stimulus. The time which elapsed between a stimulus and the change in resistance as shown by the galvanometer suggested some change in the sympathetic nervous system or in some part controlled by it. The sweat-glands seemed to have more influence than any other part in the reduction of the resistance. If the sweat-glands were stimulated there would be thousands of liquid connections between the electrodes and tissues and the resistance would be much lowered. Experiments were made by placing the electrodes on different parts of the body and it was found that the reduction in resistance was most marked in those places where the sweatglands were the most numerous. It is well known that sensory stimuli and emotions influence the various organs and glands, heart, lungs, sweat-glands, etc. Heat and cold also influence the phenomenon, heat causing a reduction and cold an increase in the resistance. In view of these facts the action of the sweat-glands seems to be the most plausible explanation of the changes in resistance. The following experiments were made in the winter and spring of 1907, with a view of determining the effect on the galvanic phenomenon and respiration of a series of simple physical and mental stimuli in a number of normal and insane test-persons. The galvanometric changes were noted by the apparatus described above. The respirations were recorded by means of a Marey pneumograph attached to the thorax and leading by means of a rubber tube to a Marey tambour to which is attached a pen-point which writes on the kymograph drum. The results of pneumographic experiments of various authors are very conflicting. Delabarre2 found that attention to sensory impressions increased the frequency and depth of the respirations. Mosso in his work on the circulation in the brain could come to no satisfactory conclusions. Mentz found that every noticeable acoustic stimulus caused a slowing of the respiration and pulse. Zoneff and Meumann found that high grades of attention cause a very great or total inhibition of respiration, while relatively weaker attention causes generally an increase in the rate and a decrease in the amplitude of the respirations. Total stoppage of respiration was found in sensory attention relatively more frequently than in intellectual. Martius notes great individual differences and comes to the conclusion that there is an affect type which differs from the normal rest and is shown by a slowness of the pulse and respiration. The experiments of the above authors were all made on a limited number of test persons, usually students. Our experiments with the pneumograph were made usually on uneducated men, attendants in the Asylum, and our stimuli were quite different from those used by the other investigators. It is possible that the great difference in our results may depend in part on these facts. In our experiments care was taken to have the conditions as nearly equal as possible. It was found that different positions of the body, leaning forwards or backwards, for example, caused a change in the level of the respiratory curves. Slight movements of the body and of the limbs did not influence the curves. The tambour itself can cause changes in the recorded curves. The tambour must contain the same amount of air in every case or the curves will be dissimilar. The curve registered is not an exact one owing to the faults of the instruments. In deep inspirations the rubber covering is rendered tense and when the pressure in the chest changes the elasticity of the rubber causes the respirations to be registered in a different way than they really occur. It must also be borne in mind that the respiratory curves recorded cannot be regarded as ordinary normal respirations but only as an experimental normal. No one can breathe naturally with a recording apparatus on his chest and with his attention more or less directed to it. The release from the tension of the experiment is well seen at the end of the experiment where the respirations become deeper and the level of the curve is changed. The pneumograph could not be used with the women on account of the clothing nor could it be used with many of the insane test persons because of their excitability. The plethysmograph was not used because the sources of error with it are too numerous. Martius has shown that even when the arm and instrument are encased in plaster of Paris involuntary movements occur which render correct interpretations of the results difficult. In the galvanic curves many sources of error must be avoided. Chief among these is the deflection caused by a movement of the hands. An increase or decrease in the pressure of the hands upon the electrodes causes an instantaneous change in the position, of the reflection of the galvanic mirror. This change is sudden and one can hardly voluntarily produce a change in the position of the reflection which resembles that caused by an affective mental process. The ordinary change of position of the hands is shown by an almost vertical rise or fall of the galvanic curve as shown on the kymograph drum. To avoid as far as possible involuntary changes of position, bags of sand were placed on the hands, thus, preventing any but voluntary movements. It was found that quite extensive movements of the body could be made without influencing the galvanometric curve. Deep inspirations, sighs, cause more or less of a rise in the curve. In the same curve a sigh occurring after an affective process seems to cause a more extensive rise than one occurring before. Voluntary long inspirations cause little or no disturbance. It must therefore be assumed that sighs are caused by some affective complex, or that they cause such a complex to come into consciousness, or that they cause an unconscious feeling state. The test-persons consist of physicians, attendants and patients suffering from various mental diseases. The experiment may be divided into six parts, each part consisting of a separate stimulus or series of stimuli of the same kind, physical or psychical. Before each stimulus or series of stimuli the test-person was told in a general way what was to occur. In many individuals after a short period of waiting for a stimulus there were changes in the respiration and in the galvanic curve due to expectation. These expectation-curves will be discussed later. The measurements of height are in each case the real, i.e., the vertical height. The respiratory rate is given as so many per centimeter which is a purely comparative measurement. In the quiet periods the average rate per centimeter for ten centimeters at the beginning and end of each period are given. Part I of the experiment consists of a quiet period of four minutes. The test-person was requested to sit as quietly as possible and was told that no stimulus was to be given. In Part II the stimulus was a leaden weight allowed to fall about three feet onto the floor. In Part III the test-person was requested to speak spontaneously, after a minute or so, a word or short sentence and then remain quiet. Part IV consists of three physical stimuli, a low whistle, a weight dropped onto the floor and a picture, picture postcard, shown to the test-person. Part V consists of four sentences spoken by the investigator. The first two were usually some familiar proverb as, "The pitcher goes to the well until it is broken"; the third and fourth were more critical and referred directly to the test-person or to his habits. In several cases single words, such as “eye” and “face,” were given. Part VI is again a quiet period of four minutes. The results of each part will be given and the normal test-persons, fifteen in number, will be first considered.

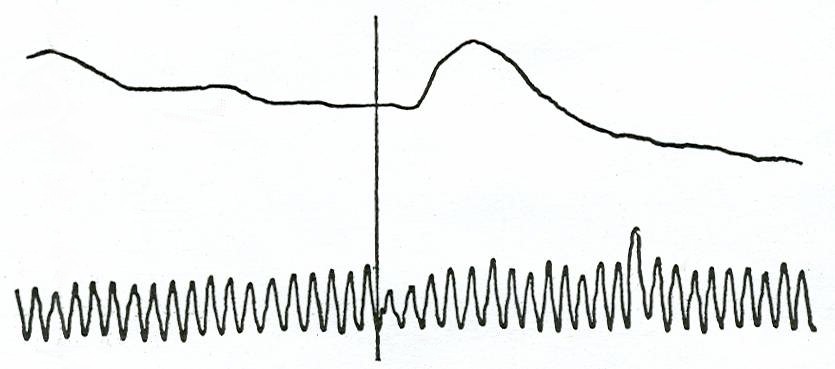

NORMAL TEST-PERSONS Part I. The galvanometric curve is usually higher at the beginning than a short time afterwards, due to the feeling of expectation and tension caused by the unaccustomed position and the strange experiment. As a rule the curve shows many irregularities caused by the movements of the hands and body which the test-person makes in adapting himself to a comfortable position, to expectation, to muscular tension, which factor, however, is not great, and to various feeling complexes. In the course of the quiet period oscillations of the galvanic mirror are seen which cannot be accounted for by any movement of the hands or body, by any respiratory change or by any conscious thought or association. We have, therefore, attributed them to the indefinite feeling caused by some complex which remains in the subconscious. Everyone has experienced these vague feelings, sad or gay, which come without apparent cause, remain but a short time and are soon forgotten. Such a curve was well shown in the case of a well-educated physician with a good power of self-analysis who could not remember any affective thought which had occurred to him during the period. The inspirations at the beginning of the quiet period are as a rule deeper and more, frequent than at the end. At the beginning they average 2.91 per cm. and at the end 2.79 per cm. The average height of the inspirations at the beginning is 12.41 mm., at the end 12.26 mm. The respiratory curve does not show any great or constant change of level in our cases. In Part II (stimulus a falling weight) the galvanometric curves show great individual differences. In one case, an attendant who was very nervous and frightened at the experiment, the galvanometric deflection was 54 mm. In another case, also an attendant, but of a very phlegmatic disposition, the deflection was only 4.6 mm. The average deflection for fifteen test-persons was 20.6 mm. The latent time, i.e., the time from the moment of stimulus to the beginning of the rise of the galvanic curve varies from 1.5 to 5.5 seconds. This time while showing individual variations is usually shorter in the cases which show the greatest galvanic reactions and averages 2.87 sec. The time required for the curve to reach its maximum height corresponds roughly to the height, a curve of 54 mm. requiring 11.5 sec. and one of 10 mm. requiring 2.5 sec. The average time is 6.93 seconds. The inspirations show individual differences in rate and amplitude and the respiratory rate does not vary as the height of the galvanometric curve, as the following table will show.

Thus the change in rate for a galvanic curve of 54 mm. is not so great as in the case of a curve of 4.6 mm. Whether the respiration is slowed or quickened during the rise of the galvanic curve seems to depend on the individual. The majority, however, show a slowing during the rise and a quickening during the fall of the galvanic curve. The average number of inspirations before the stimulus is 3.05 per cm., during the rise of the galvanic curve 3.02 cm., and during the fall 3.09 per cm. The amplitude of the inspirations does not vary directly with the rate. Before the stimulus the average height of the inspirations is 11.75 mm., during the rise of the galvanic curve 10.73 mm., and during the fall of the curve 11.45 mm.

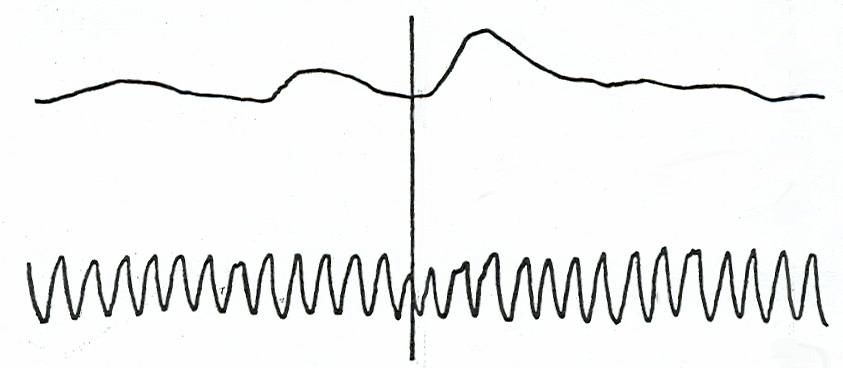

Part III (spontaneous speaking). In this part the average height of the galvanic curve is less than in the preceding, being 17.9 mm. As a rule the curves of the different testpersons show little variations in height. Some of the curves show irregularities before the moment of speaking, caused partly by indecision and partly by the preparation for speaking. In the normal test-persons the galvanic curve begins to rise with the moment of speaking or even a little before the moment of speaking. The number of inspirations per centimeter is decreased during the rise of the galvanic curve and continues to decrease as the curve falls. The average rate before speaking is 3.5 per cm., during the rise of the galvanic curve 3.15 per cm., and during the fall 3.04 per cm. The average height of the inspirations before speaking is 10.08 mm., during the rise of the curve 10.57 mm., and during the fall 11.75 mm. Thus the height increases as the rate decreases. In Part IV the stimuli are three in number: a falling

weight, a whistle and a picture. In each case the stimulus is not merely a sensory, visual or auditory one, but has also a psychical component. Practically every stimulus when perceived or received into consciousness is associated with affective complexes. A low whistle is heard not only as a sound, but also as a call and is associated with many past experiences; a picture calls up many other associations. Naturally the personal equation comes into play here to a very great extent. The results are:

In these cases the latent time increases as the height of the galvanometric curve. The time for the curve to reach its maximum varies in the different cases.

The respiratory rate in every case is increased during the rise of the galvanic curve and in one case decreased and in two increased during the fall. The amplitude of the respirations varies in the same way, being less during the rise and increasing in height as the affect passes off. Expressed in tabular form the results are:

Part V, four short sentences or words were used as stimuli. The sentences were spoken by the investigator and time was allowed between each for the galvanic curve to return to its lowest level. The results are:

As will be seen in the table the height of the galvanic curve gradually decreases in the second and fourth sentences, while the curve of the third sentence is higher. The gradual decrease in the height of the galvanic curve is to be expected and can he explained by the gradual exhaustion of the affect. The first two sentences were trite ones, and the third was usually one referring to the test-person or one that he could refer to himself, hence the stronger innervation and the increase in the height of the galvanic curve. The latent time and the time required for the curve to reach its maximum height bear no constant relation to the height of the galvanic curve. The respiratory curves vary greatly in the different sentences. In two sentences the respiratory rate is decreased and in two increased during the rise of the galvanic curve. The amplitude of the inspirations is always less while the galvanic curve is rising, while the affect is acting, and slowly increases as the affect passes off as the following table will show:

Part VI is a second quiet period of four minutes. As a general rule this part shows fewer irregularities than the first, due to the fact that the test-person had gotten accustomed to the experiment and is comfortably fixed in his place. One marked feature of this part is the change of level of the respiratory curve as soon as the test-person is told that the experiment is ended and he is released from the involuntary tension in which he has been held. The respiratory rate is slower than in the first quiet period. At the beginning the inspirations are 2.41 per cm., as compared to 2.91 per cm., in the first curve. At the end they are 2.71 per cm. as compared to 2.79 per cm., in the first curve. The height of the inspirations is 12.57 mm., at the beginning as compared to 12.41 mm., in the first curve and 12.17 mm., at the end as compared to 12.26 mm., in the first curve. What we have designated as expectation curves are changes in the galvanic curve which occur while the testperson is waiting for the stimulus. Naturally they vary according to the individual. Some of our test-persons had absolutely no sign of an expectation curve while others had quite marked ones. These curves are more frequent in the early part of the experiment and are especially marked

in Part II while the test-person is waiting for the fall of the weight. In height they vary as the reactions to the stimuli but are nearly always lower than these. The average height of expectation curves is 15.70 mm. This high average is due to the fact that a test-person who has a great galvanic reaction to a stimulus will have many and great expectation curves. The time required for the curve to reach its maximum averages 10 sec., and to fall to the former level 12 sec. The inspirations from the beginning to the top of the curve average 3.06 per cm., and during the fall average 3.3 per cm. The average respiratory amplitude during the rise is 10.18 mm., and during the fall 10.56 mm. That the individual differences in the galvanic reactions are great will be seen by the average of distribution of the various averages.

This coefficient was obtained by taking the average of the sum of the differences between the average of all the figures and each figure. It shows, when large, that there is a great diversity in the numbers of which an average is taken, when low, that the numbers are nearly equal. Two of our test-persons had extremely high galvanic curves and therefore the average and coefficient is greater than would have been the case had these two cases been omitted. Our averages, on this account, are probably higher than other observers will obtain. The pneumographic results are interesting because they differ from those obtained by other investigators and because they show a different relation between the rate and amplitude than one would expect. The following table will show the averages of all the averages of respiratory rate and amplitude and the average of distribution of each:

As will be seen the respiratory rate increases from the moment of the stimulus while the amplitude decreases during the action of the affect and increases when it passes away. The coefficients in all cases are low, and show that the numbers of which an average was taken are about equal. The relation between the respiratory rate and amplitude during the rise and fall of the galvanic curve and the high and low galvanic reactions is interesting. These relations were obtained by taking the averages of the sums of the respiratory rates and amplitudes of the high and low reactions of each individual before and after the stimulus. They are:

Thus during the rise the decrease in rate is practically the same in both high and low reactions but the decrease in amplitude is greater in the greater reactions.

During the fall of the galvanic curve the rate decreases more in the greater than in the lesser reactions, while the amplitude also increases more in the greater than in the lesser reactions. During the rise of the curve it is probable that part of the bodily innervation is expended on the various affective muscular tensions, etc., and consequently the greater the individual reacts with other innervations the less will be expended on the respiration. This would explain the decrease in rate and amplitude in the greater reactions. During the fall of the galvanic curve the innervation is probably returned to the respiration but chiefly to the depth, the rate is slowed in some of the greater reactions. The relations of the rate and amplitude before and after the reaction show that there is an increase in the rate and amplitude after high reactions and a decrease in the rate and increase in the amplitude after low reactions. The following table was obtained by comparing the rate and amplitude before the stimulus with the rate and amplitude during the rise of the galvanic curve and the rate and amplitude during the fall of the galvanic curve with that during the rise of the galvanic curve.

This table shows clearly that the differences in the respiratory changes are much greater in the cases of the higher galvanic reactions. As far as could be determined there was no regular relation between the height of the galvanic reactions and the individual bodily resistance at the beginning of the experiment.

ABNORMAL TEST-PERSONS These test-persons consisted of patients suffering from epilepsy, dementia praecox, general paralysis, chronic alcoholism and alcoholic dementia and senile dementia. The conditions of the experiment are exactly the same as in the case of normal test-persons except that in many cases the pneumograph could not be used. Epilepsy. There were nine test-persons in this group, the majority being in quite a demented condition. Included is one case of traumatic epilepsy on a basis of congenital imbecility and one case of epilepsy with hysteria. One test-person was examined immediately after an attack of petit-mal. In this case the reactions to ordinary stimuli were slight or nil, but when threatened with a needle there was a galvanometric deflection of 20 mm. This change was very slow and the curve remained high for several minutes. The threat of a prick of a needle is a very strong stimulus and causes reactions in practically every case where dementia is not marked. In this case the whistle produced a fluctuation of 4 mm. and the weight one of 2.8 mm. The other stimuli were without effect. The latent time for the whistle was 5 sec. and for the needle 15 sec. It required 21 sec. for the curve produced by the needle to reach its maximum. In this group the differences between the reactions to physical and psychical stimuli are more marked than in normal test-persons. The quiet period in all cases shows little change. Only one test-person shows what could be considered as an expectation curve. Five test-persons reacted to the falling weight, Part II. The reactions vary from 3.2 mm. to 35.6 mm. The greatest reaction was in the case of epilepsy and hysteria. The three cases not reacting were in a very demented condition. The averages for the cases reacting are,

The pneumographic results are:

The galvanometric reaction is only about one-third as high as the normal. The pneumographic results are practically those of the normal cases. Spontaneous speaking (Part III) could only be tried in three cases. In these cases there was a latent time averaging 2 sec., as contrasted with the normal cases where the curve begins to rise with the moment of speaking. The results for three cases are:

These results are less than in the normal test-persons. The pneumographic results are:

In the normal cases the amplitude decreases from the moment of stimulus; here it increases. Part IV. Three physical stimuli, weight, whistle and picture failed to cause any reaction in three demented cases. The results for five cases are:

In the normal cases the reaction to the picture was greatest. That to the weight, the one calling up the fewest associations, causing the least. The pneumographic results in three cases are as follows:

In the normal cases the height is always less during the rise of the galvanic curve, here it varies very much. Part V, sentences caused comparatively slight reactions in all cases. In four demented cases there were no reactions. The results for four cases are:

The reactions decrease in intensity from the first to the third sentence. The pneumographic curves give the following results:

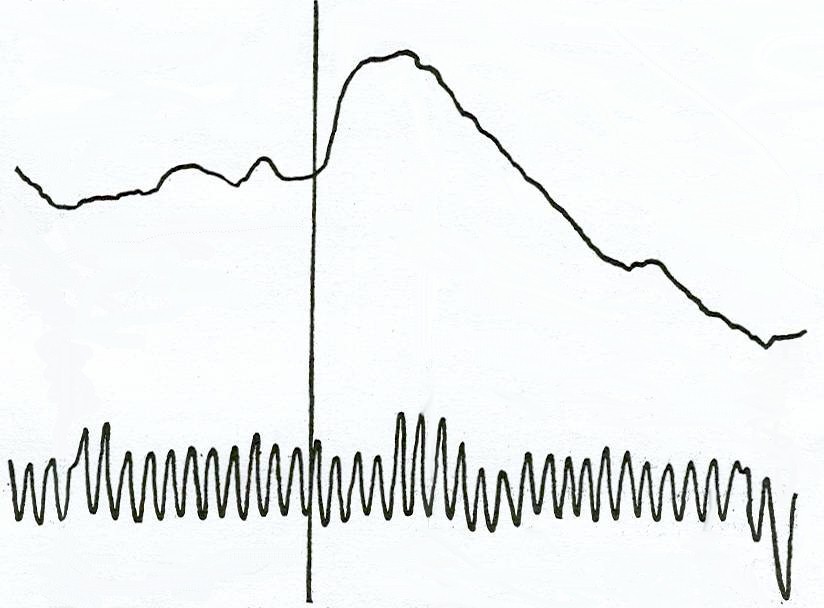

Part VI. The second quiet period shows nothing. In all these cases of varying degrees of dementia the galvanic fluctuations were in direct relation to the degree of mental dulling, the very demented having little or no reaction. In very demented cases the reactions are similar to those of the person cited above after an attack of petit mal, only those stimuli tending to cause pain are reacted to. The problem of this phenomenon is entirely a question of lack of associations. DEMENTIA PRAECOX The cases in this group were in various stages of the disease. The reactions, therefore, vary very much in the different cases. Each form of the disease will be discussed separately. CATATONIA There were eleven cases of catatonia varying from those in complete stupor to those in a convalescent condition. Our results are high because one convalescent gave reactions which were those of a normal person. Cases in a condition of stupor give practically no reaction to ordinary stimuli and in those in a depressive state the reaction is also less marked. The quiet curve varies according to the condition of the test-person. In patients who are actively hallucinated it is very often quite irregular; in patients in a stuporous condition it is practically a straight line. The pneumograph was not used. Part II (falling weight) caused a reaction in practically every case, the reaction varying from 1.8 mm. in a very depressed patient to 6 mm. in a patient with active hallucinations and 43.2 in a convalescent. The average deflection for eleven cases was 6.8 mm. Part III (spontaneous speaking) was not possible with these test-persons. Part IV (three physical stimuli) caused various reactions as in the normal cases. In five cases the whistle caused no reaction, the patients being in a stuporous, depressed condition. The weight caused a deflection of 6.3 mm;, the whistle 2.4 mm., and the picture 3.9 mm. As in the groups of epileptics the weight caused the greatest reactions. Part IV (four sentences) in every case gave reactions less than the physical stimuli. The test-person who reacted to the weight with 43.2 mm. reacted to the sentences with a deflection of from 6 to 14 mm. The averages for four sentences are:

The second quiet curve shows nothing.

HEBEPHRENIA There were eleven test-persons suffering with this form of the disease. The results while not differing markedly from those of the former group are quite different from the normal. As in the former group, the quiet curve is irregular whenever the patient has marked hallucinations. The weight (Part II) caused a less marked reaction than in the former group the average deflection being 5 mm. Spontaneous speaking (Part III) in four cases gave an average deflection of 2.6 mm. The three physical stimuli (Part IV) caused the following reactions: weight 6.8 mm., picture, 4.4 mm., and the whistle 3.5 mm. As in the former groups, the weight caused the greatest reaction. Part V (sentences) causes a greater reaction here than in the former group but a much smaller average reaction than the physical stimuli. The results are:

PARANOID GROUP There are four test-persons in this group, one in an early stage, two somewhat demented and one very demented. The latter reacted to none of the stimuli. The pneumograph was used in two cases. The quiet period is practically that of a normal testperson. Part. II (falling weight) called forth reactions less than those in the two preceding groups, the average being 4.8 mm. The latent time averages 3 sec. and the time required for the curve to reach its maximum 7 sec. The rise and fall of these curves is much slower than in the normal cases. The pneumographic results of two cases are:

These are practically the results obtained in the normal cases. Part III (spontaneous speaking) was tried in two cases, giving an average deflection of 4.6 mm. The pneumographic results are those of the normal cases.

Part IV (three physical stimuli) gives results which resemble those of the normal test-persons in that the reaction to the picture is the greatest. The results are:

The pneumographic results in regard to the depth of inspirations are practically those of the normal test-person. The rate varies in every case apparently without rule.

Part V. The reactions to the sentences are but little higher than those in the other forms of dementia praecox. The results are:

The pneumographic curves for the first two sentences only are given, those of the other two being unfit for use.

The second quiet curve is regular in all cases.

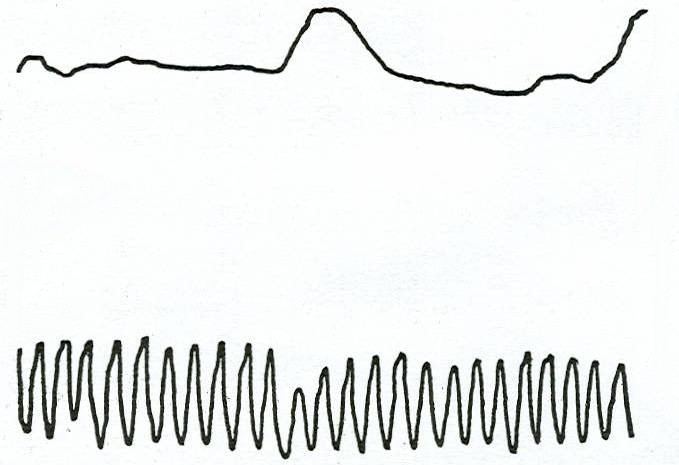

CHRONIC ALCOHOLISM There are three cases in this group, confirmed alcoholics, but showing no dementia. The galvanometric results only are given. The reactions were fairly rapid and in the majority of instances were greater to all stimuli than were those of the normal test-persons. The first quiet curve shows nothing. Part II (falling weight) caused a deflection of 2.3.3 mm., greater than in any of the other groups. Part III (spontaneous speaking) caused a deflection of 18.6 mm. Part IV (three physical stimuli, weight, picture and whistle) caused the following deflections: weight 2.4 mm., whistle 2.4 mm., picture 2.8 mm. These reactions are greater than those of the normal test-persons. The relation of the reactions to the various stimuli in these cases and in normal cases is practically the same in all cases that to the picture being the greatest and those to the weight and whistle being practically the same. Part V (the four sentences) caused reactions generally greater than in the normal cases, being, 1. Sent. 8.6 mm., 2. Sent. 16 mm., 3. Sent. 2.0 mm., 4th. Sent. 14 mm.

ALCOHOLIC DEMENTIA There were three cases of alcoholic dementia which may be contrasted with the former group. In this group the reactions are all less than in the cases without dementia and especially striking is the lessened reactions to the psychical stimuli. The weight caused a deflection of 9.06 mm. as compared to the 2.3.3 mm. of the former group. Spontaneous speaking caused a reaction of 6.8 mm. The reactions to the three physical stimuli, weight, picture and whistle are very interesting. The picture caused a deflection of only 7.6 mm., as compared to the weight 16 mm., and the whistle 13mm. The reactions are directly proportional to the physical nature of the stimuli. The picture which in normal cases caused the greatest number of associations and the greatest affects here causes the fewest associations and slightest reactions. The reduction of the reactions to mental stimuli is again well seen in the sentences where they are slight.

The lessening here is proportionally much greater than in any of the other groups.

GENERAL PARALYSIS Nine cases of general paralysis were examined. Two were in a condition of euphoria and one in a period of remission. The other six cases were in a condition of dementia and apathy and gave practically no reactions to the various stimuli. The quiet period in the cases of dementia shows nothing at all; in the other cases a few irregularities are seen. Part II (the falling weight) caused good reactions in the two euphoric cases and the case in a remission but no reaction at all in the demented cases.

The pneumographic results in these cases are practically normal.

In the cases not giving a galvanic reaction the pneumographic results for two cases are:

Spontaneous speaking could not be attempted. The following table gives a collective view of the galvanic results of all the test persons.

The above table shows that in every case the physical stimuli cause a less galvanic fluctuation than do the psychical, but in the cases where intellectual deterioration is marked the reduction is proportionally greater than in the other cases. The intensity of the reaction seems to depend in part on the attention paid by the test-person to the experiment. In cases of dementia praecox where the internal complexes dominate the affectivity and attention the reactions are slight; in alcoholism and in general paralysis, euphoric state, where the excitability is very great, the reactions are correspondingly greater. In organic dementia where all associative power is lost the reactions are almost nil. In dementia senilis where dementia was very marked even a prick of a needle failed to cause a response. The pneumographic results in these cases are practically those found in normal cases. There is evidently no rule for the rate but as a general thing the amplitude decreases during the action of the galvanic phenomenon. That the galvanic fluctuation is caused by the psychical and not the physical factor of a stimulus is shown, by the following facts: The reaction is greatest where the stimulus is such as to call up a great number of associations, e.g., the picture. A stimulus which causes doubt and perplexity is accompanied with a marked galvanic fluctuation, e.g., where the stimulus is a simple word. In cases of dementia where associations are few the reactions are correspondingly decreased. The physical intensity of a stimulus does not bear any regular relation to the size of the galvanic reaction. The strength of the reaction changes exclusively along psychological constellations. This is shown beautifully in one normal case where an ordinary whistle caused but a small reaction, but the whistle call of the society to which the test-person belonged when he was in school caused a very great galvanic fluctuation. If the attention is not directed to the stimulus the reaction is small or nil. Therefore we have no reactions in those cases where the attention is seriously disturbed. This can be proven by letting the test-person count or make lines on a paper at the stroke of a metronome. In this case the reactions are practically nil.3

SUMMARY From the above experiments we conclude that: 1. The galvanic reaction depends on the attention to the stimulus and the ability to associate it with other previous occurrences. This association may be conscious but is usually subconscious. 2. Physical stimuli as a rule cause greater galvanic fluctuations than do the psychical in our experiments. This may be due to the fact that they occurred before the psychical stimuli, early stimuli nearly always causing greater reactions than do later ones. 3. While the normal reactions vary greatly in different individuals, they are as a rule always greater than pathological reactions. 4. In depression and stupor the galvanic reactions are low because the attention is poor and associations are inhibited. 5. In alcoholism and in the euphoric stage of general paralysis the reactions are high because of the greater excitability. 6. In dementia the reactions are practically nil because of the lack of associations. 7. The reactions show great individual variations and within certain, rather wide, limits are entirely independent of the original bodily resistance.

The pneumographic results may be summarized as follows: 1. The inspiratory rate varies according to the individual and no general rule can be given. 2. The amplitude of the inspirations is generally decreased during the rise of the galvanic curve. 3. This decrease in the amplitude, however, has no relation to the height of the galvanic curve but varies according to individuals. 4. In cases of dementia where there is no galvanic reaction the changes in the respirations exist but are very slight.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

_________ 2 Remarks of Delabarre, Mosso and Mentz are quoted from Zoneff and Meumann. 3 Disassociation Experiments, by Binswanger. Jungs' Diagnotische' Assoziationstudien, XI. Beitrag.

|