|

Home Boris Menu Galvanic Research Menu Laboratory Instruments Used Part II .pdf (full article)

THE NATURE OF THE GALVANIC PHENOMENON I The purpose of our present paper is to establish rigidly the fact of the presence of galvanometric deflections under the influence of psycho-physiological processes and to investigate the nature, causation and conditions under which such deflections become manifested. It is by no means an easy matter to disentangle the conditions, physical, physiological and psychological, under which galvanic deflections appear, when an organism becomes subject to external or internal stimulations. Even when the galvanic deflections due to stimulations are established still the nature and causation seem to be beyond our grasp as the factors are numerous, the conditions complicated and the whole subject of the psycho-physiological galvanic deflections appears to be intricate and shrouded in obscurity. Investigators of the subject have declared it to be a difficult one and have been unable, except for a few conjectures, to trace scientifically by means of experimentation the cause of the 'galvanic phenomenon.’ We think that our investigation will not only establish the fact of the galvanic phenomenon free from all artefacts, but will also clear the subject of all its inherent obscurities and help to disclose its nature and causation. If may be well to add that the present study is a continuation of the work carried out by Sidis and Kalmus and published in THE PSYCHOLOGICAL REVIEW for September and January, 1908, 1909.

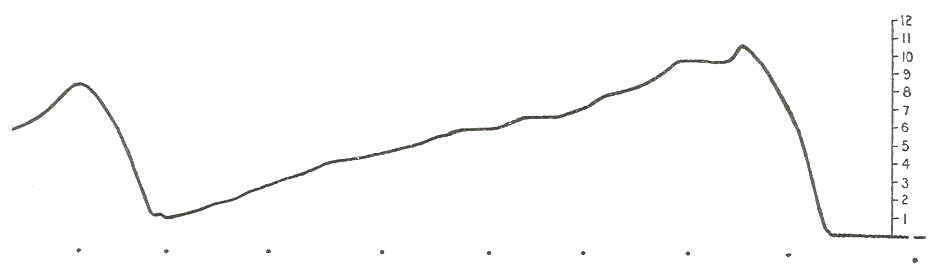

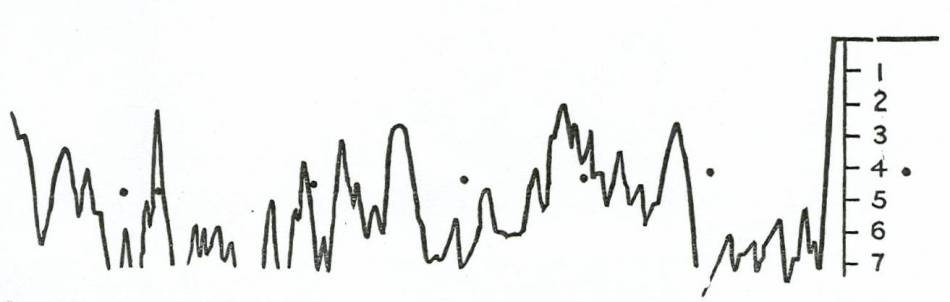

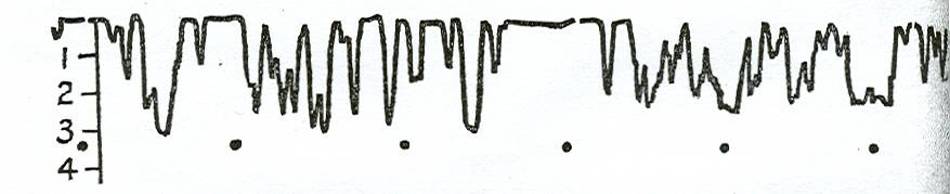

II Tarchanov is regarded as one of the first investigators who discovered the interesting fact that psychic states give rise to galvanometric deflections. According to Tarchanov all psychic processes, sensory, emotional and even purely ideational, as imagination and calculation, are accompanied by galvanometric variations. He observed large galvanometric deflections apparently brought about not only by sensory stimulations, actual affective states and emotions, but also by the mere memory and representation of such states. Intellectual processes, ideas, images, logical reasoning, memories are sufficient to affect the mirror-galvanometer and give rise to marked deflections. As a result of his investigation, published in a brief preliminary communication, he conjectures that the deflections be due to secretory changes going on in the epidermis. He is inclined to think that psychic activities affect the secretions of the skin which in their turn produce the marked deflections observed in the mirror-galvanometer. Tarchanov has not followed up his preliminary communication with a detailed study of the phenomena. Ch. Féré2 may also be regarded as one of the pioneers who pointed out the presence of galvanic changes under the influence of emotional states. According to this investigator the changes are due to variations of bodily resistance; in other words, Féré seems to think that emotional states lower the electrical resistance of the body. This assumption of lowering of bodily resistance has been uncritically accepted by many investigators. It is accepted even by those who otherwise follow Tarchanov and assume the alleged factor of skin secretions. It is assumed that the galvanic deflections are due to lowering electrical resistance through the agency of skin secretions produced by psychic activities. The cause of the phenomenon is still regarded as unknown. We shall point out that the sole cause of the obscure factor of resistance is a faulty reasoning and a deficient technique. A number of investigators such as Sticker,3 Sommer,4 Sommer and Fürstenau,5 Veraguth,6 Jung,7 Binswanger8 and others have advanced various views as to the possible causation of what has become known in psychopathological literature as the 'galvanic phenomenon.' Sticker rejects Tarchanov’s hypothesis of skin effects and action of sudorific glands as the cause of the observed galvanometric deflections under the influence of psychic states. He advances the hypothesis of circulation,―the galvanic phenomenon is the effect of circulatory changes in the capillary blood vessels, changes induced by psychic states in general and by emotional states in particular. In this respect Sticker agrees with the French investigators who unhesitatingly assume the hypothesis of circulation. The galvanometric perturbations are supposed to be the effect of circulatory disturbances which somehow lower the peripheral and bodily resistance. R. Vigoroux9 and later A. Vigoroux10 experimenting on clinical cases reject the view that the lowering of resistance is due to skin secretions; the electrical perturbations are ascribed by them to variations of resistance of blood circulation especially of the capillary blood vessels, variations of electrical resistance in some unknown way, probably by an increase or decrease of the concentration of the blood, brought about by the influence of mental states, especially by emotions. Recently C. G. Jung, of Zurich, and his collaborators, Peterson11 and Ricksher,12 have carried out a series of experiments on a number of sane and insane persons. They confirm the presence of the so-called 'galvanic phenomenon' accompanying the various mental states under observation. They find galvanometric perturbations in different forms of mental states. Jung regards the galvanometer as a valuable instrument in the study, analysis and discovery of so-called 'suppressed complexes' otherwise revealed by the so-called 'psycho-analytic method.' Some of the followers of the German school hail the galvanic test as a method in the study of psychopathic diseases in general and of hysterical affections in particular. Even criminology, it is claimed, may derive some benefit from the galvanic test, inasmuch as certain classes of criminals may be detected by means of the galvanic phenomenon. Jung and his collaborators have not contributed anything to causation of the galvanic phenomenon, but they are inclined to accept Tarchanov's hypothesis that the galvanometric perturbations are the effect of skin secretions. According to the Zürich investigators mental activities with their accompanying affective states give rise to secretions of the sudorific glands with a consequent lowering of electrical resistance which is the cause of the observed galvanometric perturbations. This conclusion is but a plausible conjecture. They think however that it is quite probable that a number of other factors concur in the causation of the galvanic phenomenon, such as circulatory changes, changes of the central nervous system and especially changes produced by mental activities and their affective states in the sympathetic nervous system. To quote from Jung, “If one applies to a subject tactile, optic or acoustic irritations of a certain strength the galvanometer will indicate an increase in the amount of the current, i. e., a lowering of the electrical resistance of the body."13 In another place Jung and Peterson, change in resistance is brought about either by saturation of the epidermis with sweat or by simple filling of the sweat-gland canals or perhaps also by an intracellular stimulation or all of these factors may be associated. The path for the centrifugal stimulation in the sweat-gland system would seem to the sympathetic nervous system. These conclusions, the authors go on to say, "are based on facts at present to hand and are by no means felt as conclusive. On the contrary there are features presented which are as yet quite inexplicable as, for instance, the gradual diminution of the current in long experiments to a most complete extinction, when our ordinary experience teaches that resistance should be much reduced and the passing current larger and stronger. This may possibly be due to gradual cooling of the skin in contact with the cold copper plates."14 As we shall see further on these investigators are on a false track, their puzzles and contradictions can be easily solved. Again Ricksher and Jung write: "The sweat glands seemed to have more influence than any other part in the reduction of the resistance. If the sweat glands were stimulated there would be thousands of liquid connections between the electrodes and tissues and the resistance would be much lowered. Experiments were made by placing the electrodes on different parts of the body and it was found that the reduction in resistance was most marked in those places where the sweat glands were the most numerous. It is well known that sensory stimuli and emotions influence the various organs and glands, heart, lungs, sweat glands, etc. Heat and cold also influence the phenomenon, heat causing a reduction and cold an increase in the resistance. In view of these facts the action of the sweat glands seems to be the most plausible explanation of the changes in resistance."15 It will be seen from our work that the Zürich school, when discussing the causation of the 'galvanic phenomenon,' has become inextricably entangled in a maze of factors which have but indirect relation to galvanometric deflections under investigation. Veraguth has been working assiduously and patiently for number of years on what he designates 'the psycho-physical galvanic reflex.' He eliminates circulation and he rightly excludes skin effects as causes of the 'reflex,' but he does not arrive at any definite conclusion as to the cause of the galvanic deflections under the influence of sensory and emotional processes. Veraguth thinks that his 'galvanic reflex' is due to variations of body-conductivity or 'Variation des Leitungswiderstandes des Körpers.' He thinks this phenomenon somewhat different from that described by Tarchanov and others. To quote from Veraguth: "Das psychogalvanische Reflex-phänomen besteht in einer Intensitätsvariation eines elektrischen Stromes der bei der Versuchsanordenung mindestens teilweise aus einer körperfremden in der Stromkreis eingescholteten Stromquelle entstammt. Es spielt deshalb bei diese Anordnung die Variation des Leitungswiderstandes des Körpers gegen diesen exogenen Strom einer Rolle bei der Variation der Stromintensitäts. Die Variation geschiet im Sinne der Abnahme der Stromintensität wenn die V.P. im Zustand der Ruhe längere Zeit in der itromkette eigescholtet bleibt. Durch diese Thatsache stellt sich ie 'Ruhekurve' im Gegensatz zu den gewohnliche bisherige Erfahrungen über anfangliche Variationen des Körperleitungswiderstandes gegen einen durchfliessenden elektrischen Strom. Die Variation veläuft im einen der Intensitäts-zunahme wenn die V.P. Reizen ausgesetzet wird. Das Moment der Gefühlsbetonung allein ist es nicht das die Stärke der galv. Reaction bedingt; es kommt auch bei den höheren psychischen Reizen. Das galv. Reflexphänomen ist also ein Indicator für Gefühlsbetonung und Actualität des psychischen Reizes. Uncontrollierbare Variabilitäten des Widerstandes in dem Stromkreisteile ausserhalb des V.P. sind ausgeschlossen; die Tatsache der Variabilität des Leitungswiderstandes des menschlichen Körpers gegen durchfliessenden Strom ist bekannt. Mit ihr haben wir also bei unseren Experimenten mit Körperfremden durchfliessenden Strom zurechnen. Nun zeigt sich aber bezüglich dieses Leitungswiderstand ein auffalender Unterschied zwischen den obigen Resultaten und der’gewöhnlichen Erfahrungen aus der Elektrodiagnostik: bei unseren Experimenten nimmt wenn keine Reize eintreten die Stromstarke stätig ab, nicht, wie wir gewohnt sind zu beobachten del' Widerstand."16 Veraguth's 'phenomenon' is an artefact. The 'Ruhecurve' which he regards as almost paradoxical is an artefact. The gradual diminution of the deflection, when no stimulations are given, is due to involuntary gradual relaxation of the grip the nickel-plated electrodes used by him in his experiments. This can be shown by the following photographic curves (read right to left):17

Sommer's attitude towards the galvanic phenomenon is rather negative. He ascribes the galvanic deflections to contact-effects between the skin and the electrodes, also to changes in the resistance of the epidermis. An involuntary increase or decrease of pressure on the electrodes would change the points of contact and skin-resistance thus giving rise to galvanometric variations. It is clear that Sommer does not regard the galvanic phenomenon as the effect of processes taking place in the organism itself. The galvanic perturbations according to Somme are rather of a purely physical character and depend on the extent of surface-contact and changes of skin-resistance Sommer's work must certainly be taken into consideration before one can establish a definite relation between psycho-physiological processes and galvanometric deflections. The usual method of most investigators, namely, the employment of metal electrodes on which the palms of the hands rest, may lend itself to such an interpretation and therefore the galvanic reaction is really not established until that objection is obviated. Jung and Ricksher do not meet Sommer's objections when they say: "That the changes in resistance are not due to changes in contact, such as pressure on the electrodes, is shown by the fact that when the hands are immersed in water which acts as a connection to the electrodes the changes in resistance still occur. Pressure and involuntary movements give entirely different deflections than that which we are accustomed to obtain as the result of an affective stimulus."18 This rejoinder is not valid as we shall see further on when we discuss the various artefacts to be avoided in order to establish the galvanic reaction. Binswanger in his extensive study of the galvanic phenomenon does not differ in his technique from that generally employed by Jung and his collaborators with whom he also agrees in his conclusions as to the nature and causation of the galvanic phenomenon. He agrees with Tarchanov that the cause of the galvanic phenomenon is the secretions of the skin "Es scheint mir in Uebereinstimmung mit Tarchanoff und trotz der Ausführpngen Stickers das es sich hier im wesentlichen um Sekretionströme der Haut (Schweissdriissen) handelt."19 In a series of experiments Sidis and Kalmus20 have affirmed the fact of the 'galvanic phenomenon' in relation to certain psycho-physiological states and have shown by various experiments that contact effects as well as skin changes and circulatory disturbances can be fully excluded as the causes of the phenomenon under investigation. Moreover, the same investigators have demonstrated that what may be called the galvanic reaction has nothing to do with lowered resistance, whether bodily or cutaneous, produced by psycho-physiological processes; they have proven that resistance can be excluded, that the phenomenon is entirely a function of an electromotive force brought about by the action of the psycho-physiological processes set up by various external or internal sensory stimulations. To quote from the original contribution: "Our experiments go to prove that the causation of the galvanometric phenomena cannot be referred to skin resistance, nor can it be referred to variations in temperature, nor to circulatory changes with possible changes in the concentration of the body-fluids. Since the electrical resistance of a given body depends on two factors―temperature and concentration―the elimination of factors in the present case excludes body-resistance as the cause of the deflections. Our experiments therefore prove unmistakably that the galvanic phenomena due to mental and physiological processes cannot be referred to variations in resistance, whether of skin or of body. Resistance being excluded the galvanometric deflections can only be due to variations in the electromotive force of the body."21 Our present work has in various ways amply corroborated the same conclusion and has definitely determined the actual cause of the observed galvanometric deflections concomitant with some psycho-physiological processes.

III From the history of the subject we may now pass to a discussion of the technique of the experiments. The usual technique of most of the investigators is very simple. In connection with a D'Arsonval galvanometer one or two cells are introduced into a circuit terminating in two metal electrodes, zinc, copper, or steel in case of hypodermic needles. The galvanometer, being shunted, the subject places himself across the electrodes usually putting one hand palm downwards on each of the electrodes, thus closing the circuit. Jung describes his apparatus as follows: "The author (Dr. Veraguth) conducts a current of low tension (about two volts) through the human body, the places of entrance and exit of the current being the palms. He introduces into the circuit the current a Deprez-D'Arsonval galvanometer of high sensibility and also a shunt for lowering the oscillations of the mirror. I add to the scale a movable slide with a visiere. The slide pushed forward by the hand always follows the moving mirror reflex. To the slide is fastened a cord leading to a so-called ergograph-writer which marks the movements of the slide on a kymographic tambour fitted with endless paper upon which the curves are drawn by a pen point. For measuring the time one may use a 'Jacquet chronograph' and for indicating the moment of irritation (stimulation?) an ordinary electronic marker."22 In their more detailed study Jung and Peterson give the following account of the apparatus employed by them: "The mirror galvanometer of Deprez-D' Arsonval; a translucent celluloid scale divided into millimeters and centimeters with a lamp upon it; a movable indicator sliding on the scale and connected by a device of Dr. Jung with a recording pen writing upon the kymograph; a rheostat to reduce the current when necessary; and one, sometimes two, Bunsen cells. The electrodes generally used are large copper plates upon which the palms of the hands rest comfortably or upon which the soles of the feet may be placed."23 Ricksher and Jung used the same apparatus with ‘brass plates as electrodes upon which the person places his hands and completes the circuit.' It will be observed that most of the investigators used electrodes, generally metal ones, without any precautions as to the traps encountered and to the artefacts produced. To avoid all those pitfalls and thus establish the galvanic reflex on a sure basis of facts Sidis and Kalmus employed the following technique: "In a series with a battery was a sensitive galvanometer across which the subject placed himself, thus closing the circuit. The battery was a single cell giving a constant electromotive force of about 1 volt which was sometimes replaced by a thermo-element giving only a few millivolts, and sometimes entirely removed from the circuit. The galvanometer was of the suspended coil, D'Arsonval type and of extreme sensitiveness. The deflections were read by means of a beam of light deflected from a mirror attached to the moving coil of the instrument, to telescope with a scale. A deflection of 1 cm. on the scale corresponded to less than 10-9 ampere through the instrument. This extreme sensitiveness was too great for many of our early experiments so that a resistance R which could be varied to reduce the sensitiveness to any desired degree, was shunted around the galvanometer. “The electrodes were glass vessels of about 4 liters capacity nearly filled with a strong electrolyte, as for instance a concentrated solution of NaCl. Into these vessels large copper electrodes of about 500 cm.2 area were permanently placed. The circuit was completed by placing the hands, feet, etc., one into each electrode solution. “The galvanometric deflections may be due to changes in the resistance at the electrodes brought about by such purely physical causes as motion or muscular contractions of the hand, stirring of the electrode fluid or similar incidental secondary effects. In order to eliminate the possibility of such effects it was necessary to devise such electrodes that the current through the circuit should, within very wide limits, be independent of the position of the hands. The possible sources of error at this point which would change the effective surface of the hands are twofold―(1) due to the variation of the liquid level at the wrist, and (2) due to movements of the hand as a whole. The following device was used to overcome those difficulties. The wrist was covered with shellac for a length of several inches, so that the liquid-surface of the electrode was always in contact with shellac. The shellac was covered by a layer of paraffin, though a moderate coating of shellac alone was such a good insulator that the electrode resistance became independent of the height of liquid on the wrist. In addition to this the hand was put in splints in such a manner that only a small fraction of the skin was covered, so that no appreciable muscular contraction of the phalanges could take place (the same skin-area being washed by the liquid electrodes). If now a stimulus was given which aroused an emotion or definite affective state in the subject, a marked galvanometric deflection was observed." After excluding resistance, both of skin and body, circulation, skin secretions Sidis and Kalmus give, as the result of their investigations, the following summary: "Our experiments thus clearly point to the fact that active physiological, sensory and emotional processes, with the exception of ideational ones, initiated in a living organism bring about electromotive forces with consequent galvanometric deflections."24 In our own technique we at first closely followed that of Sidis and Kalmus with the only difference that our subjects were not human beings, but rabbits and frogs. In the course however of adaptation of the technique to the special conditions of experimentation as well as in our efforts to eliminate complicating factors and have the results free from artefacts the technique has become substantially modified. We shall give an account of these important modifications as we proceed with the exposition of the results of our investigation.

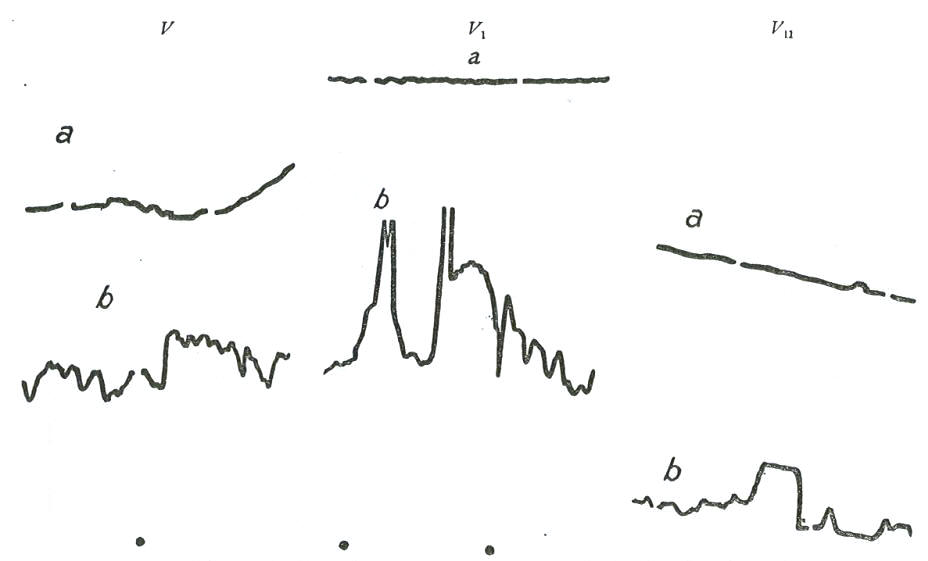

IV Before however we give an account of our technique and its gradual modification in its adaptation to the needs of the experiments in hand, it is well to give a brief review and possibly a short discussion of the main artefacts to which this work is subject. In carrying on experiments on such an intricate problem where the factors, physical, physiological and psychological, are so numerous and complex special care must be taken to avoid the artefacts which are sure to creep in and vitiate results. The first requirement in such work is simplification of the technique so as not to introduce conditions which are apt to complicate matters and obscure the possible solution of the problem. The conclusion arrived at by Sidis and Kalmus, differing widely from that arrived at by earlier investigators, namely, that the galvanic phenomenon is not due to resistance, whether of skin or of body, but to an electromotive force, helped us materially in the simplification of the conditions of the experiments, a simplification which those investigators have, afterwards adopted in the course of their work. This simplification consists in the discarding of the electric batteries introduced into the circuit. The introduction of electric cel1s is apt to mislead the investigator from the very start, inasmuch as he is unconsciously led to postulate that the resultant galvanometric deflections are due to resistance. He assumes that the only electromotive force present is the one derived from the cells and which is therefore constant. Since the strength of the current C is = E/R and as E or the E.M.F. of the cells is constant the variations of the current C which give rise to the deflections of galvanometer must necessarily be due to variations of R, that is, of resistance. Since resistance R consists of two elements (1) resistance r1 of the physical system, cells, electrodes and galvanometer, and (2) resistance r2 of the body; since again resistance r1 is constant, it necessarily follows that galvanometric deflections are due to variations of resistance of the elements or tissues of the body. It is this faulty technique of using cells from which the E.M.F. is supposed to be derived and passed through the body of the test-person that has given rise to the unproved assumption that the variations of the current which produce the galvanometric deflections are due to lowering of bodily or tissue-resistance. It is clear, if we make no assumptions, that in the formula E/R the variations may take place either in E, or in R, or in both. In other words, the unbiased experimenter realizes at the start that he deals here with electromotive forces and resistances which either alone, or both, may participate in the causation of the observed galvanometric deflections. While therefore it is a fundamental fallacy, a petitio principii as it is termed in logic, to make at the outset the unwarranted assumption of ascribing the galvanic effects to variations of only one of the factors, namely, resistance, it is on the other hand a serious error of technique to use cells in the circuit and thus complicate unnecessarily the conditions of the experiment. The introduction of more elements, of cells and shunts, brings in more electrodes and resistances into the circuit and thus only helps complicate and obscure the investigation of an intricate subject. We must remember that the first requirement of an experimental work is not complication, but elimination and simplification. If we examine more closely the conditions of experimentation of the various investigators, we find that one of the most serious artefacts results from the employment of metal electrodes, such as copper, zinc, nickel, brass and steel in direct contact with the fluids of the palmar surfaces of the Calomel-mercury electrodes present similar artefacts on account of the impurities giving rise to currents with sudden and often ceaseless fluctuations of the mirror-galvanometer thus causing extensive artefacts seriously impairing the value of the results. One cannot help realizing the full force of Sommer's objections that under such conditions numerous variations of contact are brought about, variations which in themselves are amply sufficient to account for the observed galvanometric perturbations. The results are at any rate vitiated and totally obscured. Under such conditions of experimentation galvanometric deflections cannot possibly be correlated with psycho-physiological changes. It can also be shown that in the use of metal electrodes the galvanometric deflections obtained when the hands are placed on the electrodes differ widely from those obtained when the same electrodes are put (passively) on the hands (see Curves V, V1, V11).

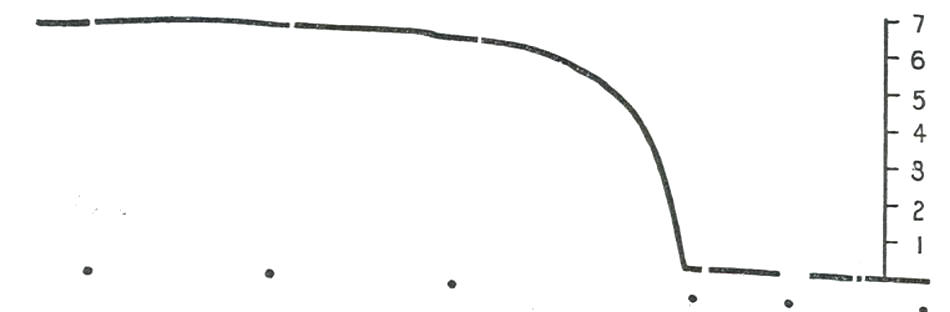

An important source of error is the employment of polarizable electrodes. The physical currents induced by polarization give rise to so many electrical variations and consequent galvanometric deflections as to destroy the scientific value of the results. The fluids of the palmar or of the skin surfaces in contact with the polarizable metal electrodes initiate a number of currents which ceaselessly give rise to large sudden deflections of the mirror-galvanometer. In cases where we have all those conditions combined, namely, increased or decreased surfacecontact and pressure accompanied with changes of polarization we can realize how unreliable and untrustworthy the final results are. The current view that the galvanometric deflections are due to skin-effects is quite in accord with the artefacts of the experiments, since under such conditions the main galvanometric deflections do occur under the various influence of skineffects. As long as the experiments are conducted under such conditions and are beset with such serious artefacts not only is it vain to expect a correct view of its causation, but even the very fact of the correlation of psycho-physiological processes galvanometric deflections cannot be established with any degree of certainty. The claim of Jung and his collaborators that “when the hands are immersed in water which acts as a connection the changes still occur" is in itself beset with many errors. In the first place, if the liquid is put in two different vessels, the liquid must be of the same concentration and of the same temperature, otherwise we get deflections due to difference of temperature and concentration; then again the least change of level of the liquid will change the level at which the electrodes are washed which will produce new currents. At the same time the change of level of the liquid will change the area of the skin washed and will once more initiate currents. Then, again, the wires and metal plates become polarized and additional currents supervene. The artefacts are here so numerous that to obtain any results is almost hopeless. Sidis and Kalmus, who worked with liquid electrodes had to contend with all those difficulties and could only circumvent and overcome them with constant vigilance for artefacts and painstaking precautions, such as the careful use of pure or distilled water of the same temperature, the use of shellac and paraffin as well as splints for the hands. The following photographic curves will give one a clear idea of the ceaseless play of currents and hence of the artefacts met with in the use of polarizable metal electrodes or of liquid electrodes when the necessary precautions are not taken.

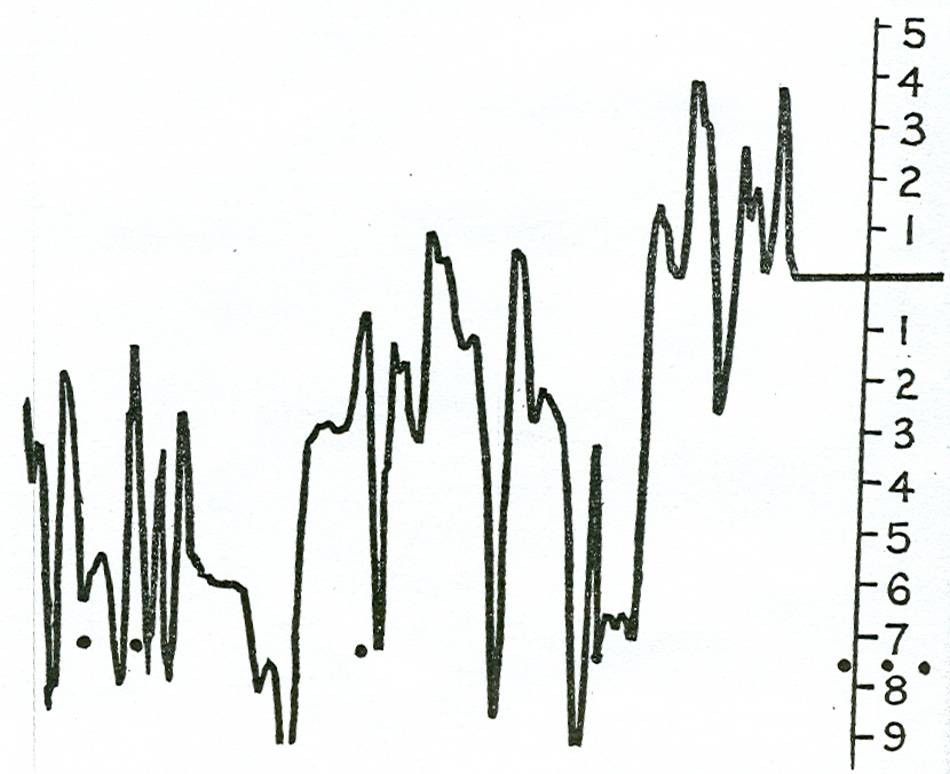

When working with hypodermic electrodes the effects of polarization should be specially taken into consideration. Steel or iron being impure becomes easily affected chemically, thus giving rise to currents with large variable galvanometric deflections. The following photographic curves obtained with steel electrodes inserted into the skin of a rabbit's abdomen bring out clearly the effects of polarization:

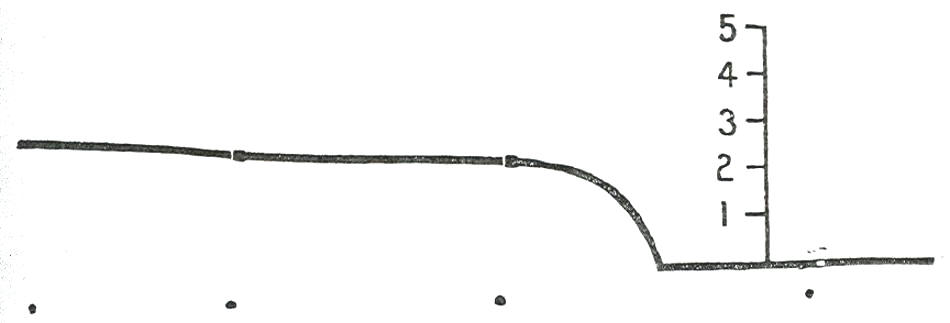

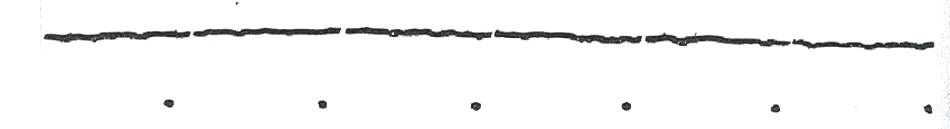

It becomes clear from what we have said how cautious one has to be and with what numerous difficulties one has to cope in the investigation of this subject. Considering then the difficulties and numerous artefacts we had to contend with it may be of interest to point out the development of our technique. As we have already mentioned the fact our work links on to that of Sidis and Kalmus and naturally our technique was the same as theirs. These investigators started with the usual procedure, common to all earlier investigators, of introducing cells into the circuit. Unlike, however, other investigators, they did not start with the tacit assumption of regarding the observed galvanometric deflections as due to variations of the factor of resistance alone. They were on the lookout for variations both of electromotive forces and resistance. Since the trend of their experimentation was clearly in the direction of electromotive forces and towards the total elimination of resistance as a factor in the galvanic perturbations, they finally in their later experiments completely dispensed with the cells and superimposed electromotive forces derived from outside sources and worked with the electromotive forces manifested by the organism under the influence of external stimulations. Such a procedure is essential as it deals directly with the phenomena under investigation. We followed the same procedure and discarded the cells. The physical system of the circuit was thus greatly simplified. Moreover, we decided to work on animals instead of test-persons who are by no means favorable subjects for experimentation. Animals present us with great scope for experimentation, for surgical operations, for the injection of various drugs and thus to afford opportunities for the study of the causation of the galvanic phenomenon and allow the exclusion of the various complicating factors not concerned in its production. Now in our experiments with animals, rabbits and frogs, we found that the technique of Sidis and Kalmus had to be further modified. In the first place the liquid electrodes with shellac, paraffin and splints proved inadequate as the hairy legs of the rabbit did not quite lend themselves to such manipulations. Shaving the hair was not satisfactory, taking it off chemically produced an undesirable inflammation unfavorable to the purpose of our experiments. Besides, the liquid-electrodes proved unsatisfactory as it was difficult to restrain the rabbit from agitating the liquid and sometimes spilling the contents of the vessels, thus changing the levels of the liquid with its consequent large galvanometric deflections. The technique was defective, because we had not only to watch the deflections, but also the rabbit, the fluid, the vessels and the wires. Another objection to liquid-electrodes is the fact that they do not eliminate skin-effects which, as it has been demonstrated, are not concerned in the causation of the galvanic reaction. We were therefore forced to give up liquid-electrodes and in order to eliminate the skin, we had to fall back on hypodermic electrodes. This procedure not only considerably simplified the conditions of experimentation, but it also, at one stroke, so to say, greatly simplified our problem, since we thus got rid of the factors of pressure, increased and decreased contact-area and of all the disturbances that might be ascribed to the action of the sudorific or sebaceous glands. The simultaneous simplification of method and problem was too important not to take advantage of. Hypodermic electrodes were clearly indicated by the conditions and nature of our work. It is however one thing to find that hypodermic electrodes are indicated and it is quite another matter to find the proper kind of electrodes. We found 'that copper, iron, steel, nickel, brass, had to be rejected, because of the ease of polarization giving rise to variable currents with consequent variations of galvanometric deflections (see Curves VI, VII, VIII). It was found that platinum is sufficiently pure so as not to become polarized and is therefore well adapted to our purpose. When using hypodermic platinum-electrodes, the galvanometer was found to remain steady as can be seen from the following photographic curve:

This steadiness of the galvanometer is of the utmost importance, because it gives us a steady zero-reading, while in the case of other investigators there is no steady zero-reading, since their galvanometer keeps on ceaselessly varying, thus making the results uncertain and even destroying their value. Platinum hypodermic electrodes were used by us throughout our work. Our technique thus far was extremely simple: a D'Arsonval type of galvanometer with scale divided into millimeters, platinum hypodermic electrodes and a key for closing and opening the circuit. Focal distance of mirror to lamp is one meter. Sensibility is 225 megohms. Period is 9.5 seconds. The sensibility is given in the number of megohms resistance through which one volt will give a deflection of one millimeter at one meter distance. The period is the time of swing from the maximum deflection to zero. We found it requisite to take photographic records of the galvanometric deflections. We shall give a detailed description the apparatus and its complete outfit in its proper place.

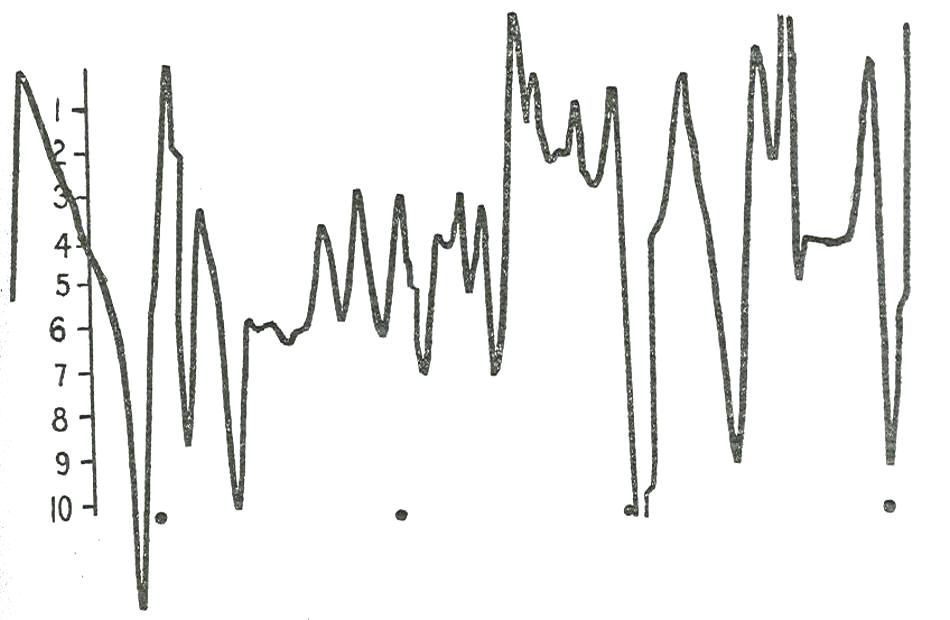

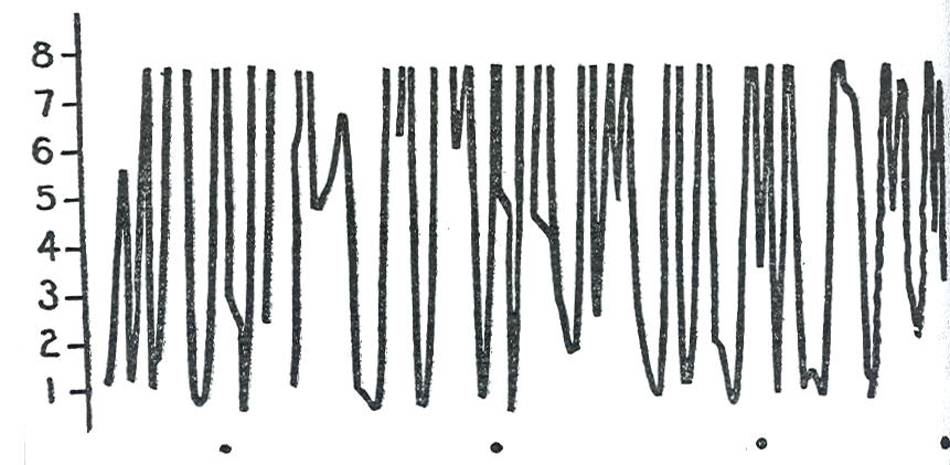

V The animal was put on an animal board and kept quiet, while the hypodermic electrodes were inserted into the body, usually well under the skin or through a muscle. We may now pass to the experiments. We quote a few experiments selected from our laboratory notes: Experiment I.―Live rabbit; hypodermic platinum-electrodes inside of thigh.

Opening and closing the circuit did not change the galvanometric zero reading.

Experiment II.―Same live rabbit; hypodermic platinumelectrodes inside of forelegs.

Experiment III.

Galvanometer then returned to its original zero reading.

Experiment IV.―New fresh rabbit. Hypodermic electrodes inserted in forelegs.

We must mention here one important point. Every time the platinum electrodes were taken out to be inserted again, whether in a new fresh animal or into the same animal, they were sterilized on a flame and thus purified from extraneous matter. This was the procedure in all our experiments. To return to our work: Experiment V.―New fresh, live rabbit.

When rabbit came out of narcotic state the galvanometric deflections under various stimulations were the same as before narcotization:

Out of the many experiments carried out on frogs we take one series as typical of many others. Experiment VI.―Live frog. Platinum electrodes inserted into each thigh.

Experiment VIII.

After strychnine took effect stimulation began to give large galvanometric deflections.

Even tapping the board produced deflections ranging from 24 to 23.70, to 24.20 and back to 24 cm.

Frog in convulsions; galvanometer keeps on oscillating from zero-reading 24 cm. to 23.80, to 24, 24.10, to 24.20 and again to 24 cm.

The summary of our experiments with various frogs runs in our note-book as follows; "Frog motionless on board, no deflection. Every time frog moves, galvanometric deflection observed. The extent of the deflection appears to be proportionate to the amount of movement. Alcohol poured on the head of the frog; reaction violent, movements very extensive, large galvanometric deflections. Strychnine 3 drops administered to frog hypodermically. At first frog was quiet, no galvanometric perturbations. Afterwards frog in convulsions, galvanometric deflections amount to 10 centimeters." The experiments in both species of animals, rabbits and frogs, give us practically the same results. Of course, should expect to find that in animals so widely different as the rabbit and the frog the extent of the galvanometric deflection would differ under the influence of external stimulations. At this stage of our work the experiments prove conclusively the following propositions: 1. Every sensory stimulation is accompanied by a corresponding galvanometric deflection. 2. Motor reactions intensify the galvanic phenomenon giving rise to a more extensive deflection. 3. Motor activity is by itself sufficient to give rise to large galvanometric variations, as found in the rabbit and more especially in the frog poisoned by strychnine. 4. The hypodermic electrodes, excluding the effects of epidermis, show that the galvanic perturbations due to external sensory stimulations are not the resultant of skin-effects. In other words, the skin is not concerned in the manifestation the galvanic reaction. This conclusion will be established more rigidly by a different set of experiments. The galvanic reaction being established by our experiments the question may be raised as to whether our experiments give us an insight into the nature of the galvanic phenomenon. Are the galvanometric deflections correlative with psycho-physiological changes induced by external sensory stimulations due to variations of resistance, lowered resistance, or are the deflections due to an electromotive force initiated in the organism itself by the action of psycho-physiological processes. We may say that our experiments prove conclusively that the galvanometric phenomenon is not due to changes of electrical resistance, but to the action of a newly generated electromotive force. If we scrutinize our experiments more closely, we find that, when the circuit is open, that is, when there is no current, the galvanometric zero-reading is 24 cm. On the insertion of the hypodermic platinum electrodes and closure of circuit there is an initial galvanometric deflection which indicates the presence of a current. This current is due to the slight injury of the tissues produced by the insertion of the electrodes and also due to difference in temperature. After a period of four or five minutes the current subsides and the galvanometer returns to its original zero-reading when the circuit is open and no current is flowing trough the system. If we now open and close the circuit, the galvanometric reading remains unchanged at the original zeroreading. In other words, there is no current on opening or closing of circuit. If now, with circuit closed and galvanometric reading at its zero-reading, we prick, pinch, burn, or stimulate the animal in various other ways, we get a galvanometric deflections which can only be brought about by the generation of an electromotive force. It is clear that no change of resistance without an electromotive force can possibly bring about a galvanometric deflection. Hence our experiments prove conclusively that the galvanometric deflections are not due to changes of resistance, but to electromotive forces. Since the hypodermic platinum electrodes exclude the effects of contact, pressure and skin, it is obvious that the galvanic phenomenon can only be due to an electromotive force initiated in the organism itself by the psycho-physiological processes under the influence of external stimulations.

_________

Home Page Boris Menu Galvanic Menu

|